Is This the Future of Health Worker Training?

Project HOPE’s online trainings are helping tens of thousands of doctors and nurses recognize and treat COVID-19. But can remote trainings replace face-to-face instruction?

For more than 60 years, Project HOPE has been training health workers to fight the health battles in the communities where they work.

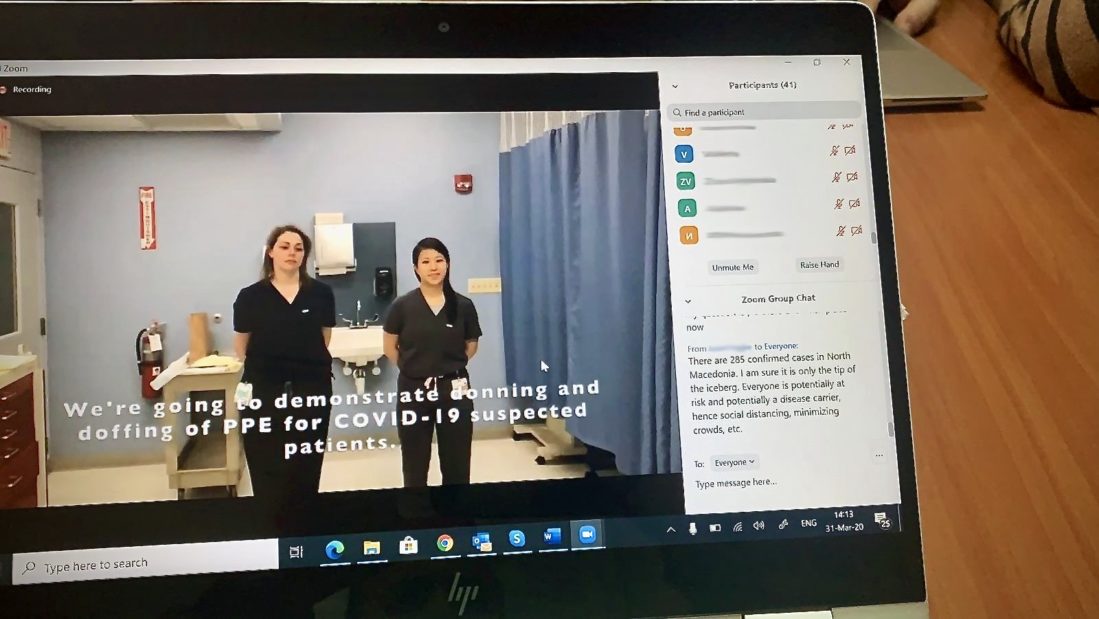

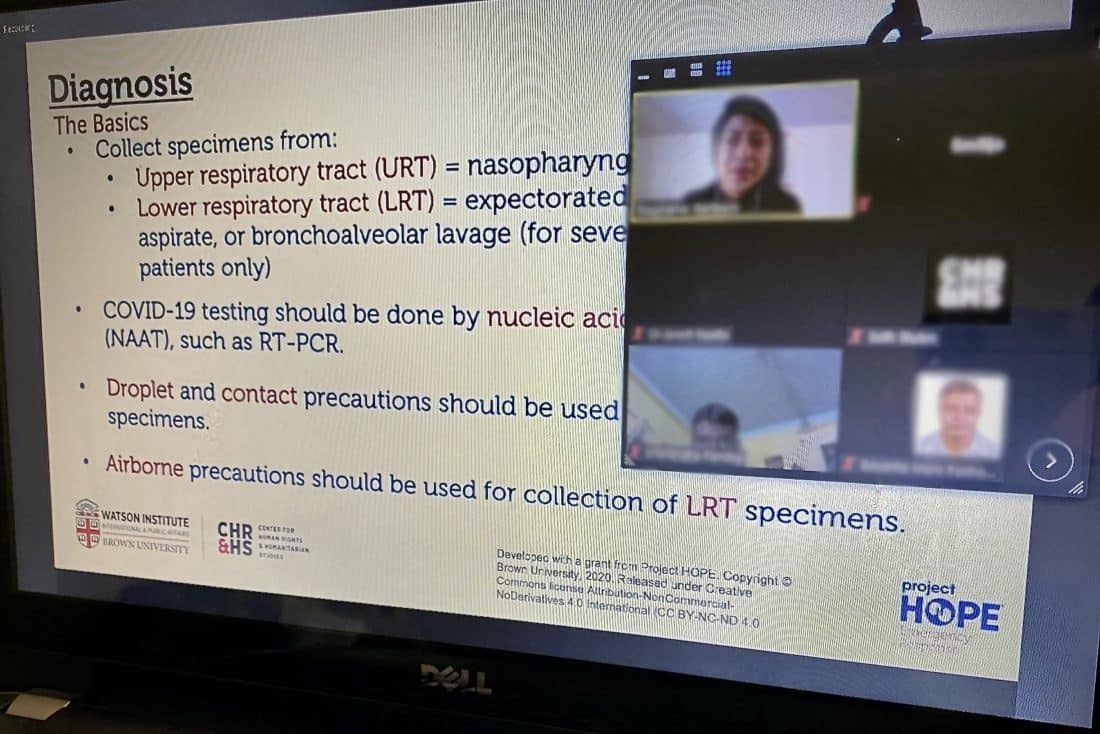

Now, the classroom is changing, as COVID-19 forces nurses, doctors, and other frontline health care workers to go virtual and learn online. In partnership with experts from Brown University, HOPE is delivering a remote COVID-19 training program for doctors and nurses to become Master Trainers in infection prevention and control, who can then train other health workers to recognize and treat COVID-19.

To date, live remote trainings have been held in 22 at-risk countries, with over 900 Master Trainers completing the training and passing it on to more than 22,330 health workers.

Dr. Tom Kenyon joined Project HOPE as president and CEO in 2015 and became its chief medical officer in 2018. He has worked in global health for nearly four decades as a pediatrician, epidemiologist, and innovator in program delivery. Read on for an interview with Dr. Kenyon on how HOPE continues to expand the reach of its COVID-19 training, and how the remote model will become “the new norm.”

What are the advantages of remote trainings like these?

Dr. Kenyon: Well in this instance, we had no other choice — there was no other way to do it. But there are a lot of advantages. We don’t have to travel. We don’t have to expose ourselves to the virus. I think there’s a cost advantage, too.

But also, we can also provide really good trainers. For in-person trainings, you couldn’t possibly travel half a dozen good trainers around the world. You might be lucky to send one or two. We had clinicians who had already seen COVID, who were somewhat familiar with it, so it wasn’t just a theoretical training — they could speak from experience.

We’ve also been able to customize training to each country’s realities and make it very comprehensive. And the format is more flexible — just a couple of hours a day — which works better with people’s work schedules.

What are the tradeoffs?

Dr. Kenyon: Well, there’s really no substitute for people-to-people training. In terms of building relationships, learning virtually is not ideal.

It’s also not as simple as just turning on your computer. You have to organize it on both ends — you have to have the right people in the room, and you have someone there who can make sure things run smoothly. It takes a lot of planning and monitoring.

It’s also harder to know the local context from thousands of miles away, especially in places where we don’t already have a strong presence. When you go for in-person training, you often visit the site or facility where you’re training the people to serve. You also meet with government officials, which helps to authenticate the training and empower the trainees to do what they’re trained to do.

Has the curriculum changed since it was launched?

Dr. Kenyon: Yes. One of the challenges of this training is to continually adapt our COVID curriculum to reflect new information. We have interventions and antivirals that work now. We know the best way to put a patient on a ventilator. There are a lot of clinical updates that we have to go back and change. That’s a challenge and an opportunity.

The reality is training isn’t everything. We know this training is just one step in the process and we’ve learned you have to follow it up with some sort of mentoring. We’re starting to use a follow-up platform called eConsults, in partnership with the Weitzman Institute, where an approved clinician (someone who has gone through the training) will refer problem cases to a panel of expert consulting physicians. The chances are that many people will have the same questions, so we’re thinking about holding periodic webinars on common themes and lessons learned.

How could this model be especially beneficial for developing countries?

Dr. Kenyon: I think this is going to become standard practice. Partly because of cost — cost is certainly a consideration — but also because of expediency and efficiency. Trainees can take it after clinic hours, and take a little piece at a time rather than missing clinical duties for two or three days — which is devastating to some of these hospitals.

Connectivity is so much better than it used to be. You wouldn’t have dreamed of this in parts of the world where we work even just a couple of years ago. But the reality is there are still some places without good connectivity — especially in the rural and more remote areas. So it would be a challenge, in some cases, to reach the periphery.

Some things Ive learned from our @projecthopeorg @BrownCHRHS #COVID19 remote trainings in #northmacedonia #kosovo #PuertoRico 1)Our actions/behaviors matter more than material resources (or lack thereof) 2)We have lots to learn from our colleagues in resource-limited areas. pic.twitter.com/1LcUlbpEVs

— Stephanie C Garbern, MD MPH (@sgarbern) April 5, 2020

What’s particularly strong about this training?

Dr. Kenyon: It’s very A to Z. It has a basic virology background component, it has a public health and infection control component, it has a clinical component that’s designed for low- and middle-income countries. It basically takes you up to the point where you would need to put someone on a ventilator.

I think what we found is most special about this training is the interaction. Typically when you do online trainings you watch a PowerPoint, answer some questions, and close the file. You don’t have a chance to talk. But with our remote training, we use a chat feature for questions and engagement.

There’s also a real skill and competency-based aspect to it. The training includes videos that are filmed in a hospital, not off in a studio, so it feels very real. Videos cover topics like how to wash your hands, how to put on PPE and how to take it off, and what to look out for during a physical examination. There are also quizzes and informative case studies that invoke a lot of discussion.

When we conferred with the Centers for Disease Control, they said it was the best curriculum they’ve seen out of all the training curriculum that they’ve had a chance to review. They shared it with every CDC country director around the world. They thought it was that good.

How is HOPE thinking about using this model beyond COVID-19?

Dr. Kenyon: I wouldn’t be surprised if this format becomes the new norm.

I’ve had some initial discussion with our group that’s working on newborn mortality. We’re thinking of trying a similar training platform to train nurses to care for sick and low-birthweight babies in Malawi and Sierra Leone. It’s a community of health workers with a common interest. I think that’s the thread in all of this. You want to bring likeminded people together. I see endless possibilities. I see potential for remote training in many areas.

But the model doesn’t teach practical skills — you can’t teach surgery or anesthesia or how to do a procedure this way. But that’s OK — what you do is you back up the virtual training with skills laboratories and on-sight clinical instructors. It would be a mixed model.

This is not a new concept, but the world is going to be millions of health workers short. We already are. And that gap is only going to widen as populations go up and health worker training doesn’t go up at the same pace. Especially for Africa — the absolute numbers are expected to increase, but the ratios of health workers to people are expected to get worse. The remote model will help us reach more health workers.

What lasting lessons will you take with you from this initiative?

Dr. Kenyon: The pandemic has reminded us of how training pays off in the long term. Some of the first nurses who responded in Wuhan were graduates of the Wuhan HOPE School of Nursing. Years ago, with embassy funding, we put on a disaster preparedness training. It would be short-sighted if we didn’t look at how to train more of these clinicians on how to deal with infection control issues.

We need to keep this training alive. That’s the bottom line. We’re still exploring what that looks like, but I think the world has to get used to this kind of social distancing. We’re facing this for the foreseeable future. We have to keep training alive and responsive, and we have to take it to scale. Training 22,000 health workers is great — but there’s millions of health workers out there who aren’t trained. How do we reach them?

Learn more

Access COVID-19 training materials

Get the latest on HOPE’s ongoing response to the pandemic

How you can help

Our ability to respond quickly when hurricanes, earthquakes and other natural disasters strike, even as we continue our lifesaving work around the world, depends on the generosity of people like you.

Please make a generous donation to our Global Health Emergency Fund today. You’ll help us prepare for emergencies before they happen and respond quickly when disaster strikes, so we can help communities around the world when we’re needed most.

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work at projecthope.org/donate.

Are you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.