Maternal, Neonatal & Child Health

Project HOPE trains and empowers local health care workers to improve maternal, neonatal, and child health.

Saving the Lives of Women and Babies

Despite incredible gains in global health care, thousands of women and infants die from preventable causes every day. If current trends hold, 60 million children will die in the next decade before their fifth birthday — almost all of them in developing countries. That is unacceptably high.

We know the causes, and we have the solutions. Nearly all of these deaths are preventable.

Project HOPE has worked to save the lives of women and babies around the world since 1985. Our strategic priority is to achieve a global community where no woman or newborn risks dying from preventable causes. That’s why we’re working every day to improve access to quality care, build the skills of health care workers, and expand community support in places where mothers and infants need it most.

Whether training midwives in Indonesia, equipping hospitals in the Dominican Republic, or launching mother care groups in Sierra Leone, Project HOPE plays a vital role in the global mission to give all mothers and babies a healthy future.

![]()

How We Provide HOPE

Project HOPE provides vital health care services for women and babies in more than 28 countries. We are a founding member of the CORE Group, and our current MNCH programs prioritize the achievement of the World Health Organization’s Every Newborn Action Plan.

Our approach focuses on helping women and infants improve their access to:

- Routine, essential care before, during, and after childbirth.

We support health care workers and facilities with skills and tools throughout the birth process. The interventions we promote include monitoring and management of labor, active management of the third stage of labor, hygienic cord care, and vaccinations within one hour of birth. We also promote vital practices like routine newborn screenings, skin-to-skin contact, and exclusive breastfeeding. - Emergency obstetric and newborn care.

Around the world, we help ensure that skilled birth attendants have the capabilities they need to provide care. That’s why we promote deliveries by skilled birth attendants, safe blood transfusions, corticosteroids for preterm labor, antibiotics to treat infection and sepsis, resuscitation training for babies with asphyxia, Kangaroo Mother Care, and the safe administration of oxygen and ventilation. - Care for sick and pre-term babies.

In Sierra Leone and the Dominican Republic, Project HOPE established a mentoring program at the district and pediatric hospital focusing on high risk/sick newborns. The program includes essential and emergency care, resuscitation, management of pre-term and sick babies, prevention of infection, and safe use of equipment. We’re also working with countries and partners to establish advanced-level education programs for advanced neonatal nurse programs for the optimal care of sick newborns. - Integrated HIV/AIDS and MNCH services.

HIV-positive pregnant women are eight times more likely to die during pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period than HIV-negative women. Our comprehensive approach reduces the impact of HIV/AIDS on maternal mortality through testing, counseling, and Preventing Mother to Child Transmission programs for pregnant women with HIV/AIDS.

Equipping the Next Generation of Neonatal Nurses

Sustainable gains in neonatal health depend on a well-trained neonatal workforce. In Malawi and Sierra Leone, Project HOPE is working to develop neonatal nursing specialty programs in order to ensure a sustainable cadre of expert nurses capable of providing state-of-the-art advanced nursing care for newborns.

Project HOPE is working with the Council of International Neonatal Nurses, nursing school and university partners, and expert neonatal nurse volunteers to help the governments of Sierra Leone and Malawi establish their first Neonatal Nursing Bachelor degree programs. Project HOPE is directly partnering with a health institute in each country and is currently assisting National Development Committees to develop curriculums and prepare faculty to teach neonatal nursing in the upcoming year.

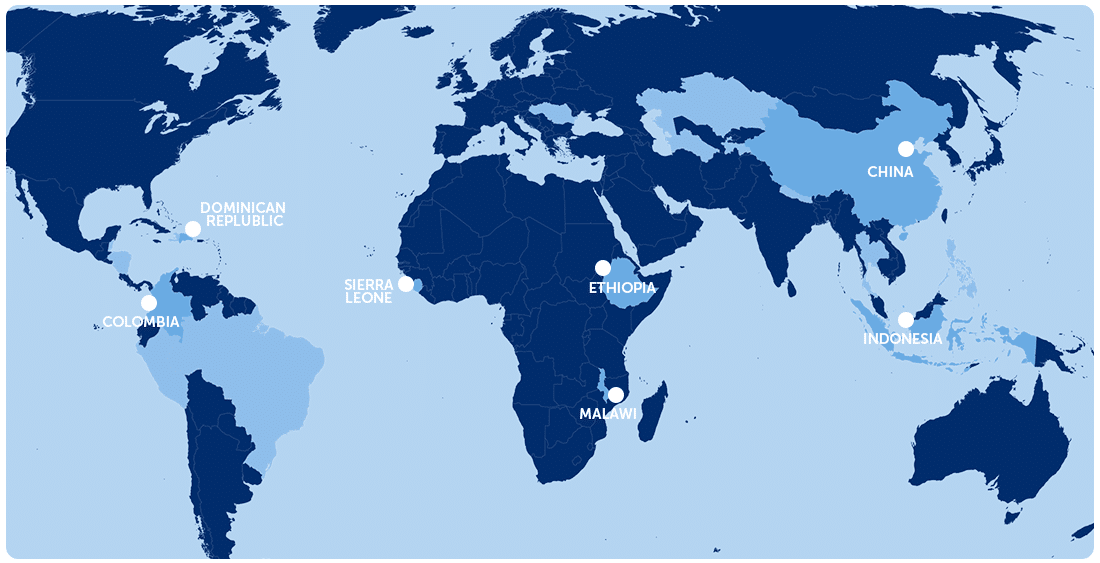

Where We Work

Our programs are changing the lives of women and babies around the world. We currently have programming in China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Sierra Leone.

Historically, we have had Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health programs in Malawi, the Philippines, Hungary, Romania, Nepal, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Peru, Haiti, Northern Thailand, and Brazil.

Achieving Results

Since the Ebola outbreak, Project HOPE has been working with the government of Sierra Leone to identify and address gaps in maternal and newborn care facilities in Freetown and Bo Districts. To date, we have trained more than 1,500 health care workers in essential newborn care that includes Kangaroo Mother Care and care measures for small and sick babies.

We’ve helped train over 1,300 hospital staff in the Dominican Republic and have assigned over a dozen new nurses to NICU units throughout the country. We’re also helping equip hospitals with radiant warmers, vital sign monitors and incubators, and are supporting the Ministry of Health in establishing a post-graduate education program to train nurses in obstetrics and neonatal care. As a key partner in newborn health programs, we have celebrated many successes. Compared to the same period in 2018, the Dominican Republic experienced a 29% decline in the neonatal mortality rate in 2019 — the greatest reduction in recent years.

In Indonesia, we are training midwives and health workers to be better positioned to manage complications at childbirth. Since 2016, this training has made the difference between life and death for more than 85,000 mothers and 11,000 newborns.

We’re providing hands-on training for health extension workers and health facility staff in areas of Ethiopia that have the highest levels of maternal and neonatal mortality. We’re also supporting regional vaccination efforts, surveilling and responding to polio cases, and are strengthening hospitals’ Emergency obstetric and neonatal care centers.

We’ve partnered with numerous national governments, child health specialists, and the private sector to create children’s hospitals in China, Poland, Iraq, and South Africa. In addition to equipment and supplies, Project HOPE sends highly qualified volunteers in pediatric medicine, nursing, and other specialty areas to train local health care workers.

Get The Facts

Maternal Mortality

Maternal Mortality

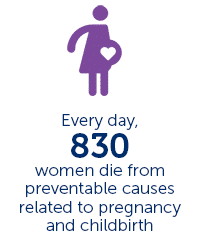

Despite great progress in reducing maternal mortality rates, the number of women who die due to complications from pregnancy and labor is far too high.

More than 800 women die every day from causes that are almost entirely preventable.

Where do these deaths occur?

Almost all maternal deaths occur in developing countries. Many of the worst countries for maternal mortality are in sub-Saharan Africa, with Chad, Central African Republic, and Sierra Leone at the bottom of the list. More than half of maternal deaths occur in fragile and humanitarian settings, where 1 in every 54 women faces the risk of death due to pregnancy complications.

What are the leading causes of maternal mortality?

Nearly three-fourths of all maternal deaths are from causes like severe bleeding, infections, hypertensive disorders like pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, and complications from delivery. These risks are particularly dangerous for girls aged 15-19, who account for more than 10% of births worldwide. Most of these complications are preventable or treatable.

Why don’t these women receive care?

There are several reasons women in these areas don’t receive care. In many places care is simply not accessible; in others, it’s unaffordable. Women may not have information about care, or cultural practices could be holding them back. One of the most serious issues facing the global community is a lack of skilled health workers, like in Sierra Leone, where 21% of the entire medical workforce died during the 2014 Ebola epidemic.

How can these deaths be prevented?

When it comes to maternal mortality, we know the causes and we have the solutions. As the WHO states, all women need access to antenatal care in pregnancy, skilled care during childbirth, and care and support in the weeks after childbirth. Risks for severe bleeding, for instance, can be reduced by injecting oxytocin. Infections can be prevented with good hygiene, and pre-eclampsia should be detected and addressed with drugs like magnesium sulfate. All of this, however, depends upon women having access to skilled health care workers in their own community.

What are the Sustainable Development Goals for maternal mortality?

As part of the Sustainable Development Goals, the WHO has set a target to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births. This amount of progress is possible: Between 1990 and 2015, the global maternal mortality ratio decreased by 44%. In sub-Saharan Africa, a number of countries have cut their levels of maternal mortality in half, while parts of Asia and North Africa have seen even greater progress. To reach this goal by 2030, however, will require serious investment in maternal health programs and policy.

Newborn Mortality

Babies are most vulnerable in the first 28 hours of life.

Even though great progress has been made to reduce the health complications babies face, 7,000 newborns die every day from causes that are relatively simple to prevent.

Where do these deaths occur?

According to UNICEF, eight of the 10 worst countries for neonatal mortality are in Africa, including Central African Republic, Somalia, and Lesotho. The worst infant mortality rate in the world (46 deaths per 1,000 live births) is Pakistan, due to insecurity and lack of access to quality health care facilities.

What are the leading causes of newborn mortality?

Most neonatal deaths occur in the first week of life. The vast majority (80%) of newborn deaths are due to preventable causes like premature birth, labor complications, and infections. Malnutrition is the major underlying factor, which makes babies more vulnerable to disease.

Why don’t these infants have access to care?

A newborn’s risk of death is tied closely to where they are born, and many of the reasons they lack access to care are the same as the reasons for maternal mortality: care is either inaccessible, unaffordable, or families lack information about it. There is also a strong correlation between neonatal mortality and a country’s national income level, with the rate for low-income nations nine times higher than the rate for high-income nations.

One of the greatest concerns regarding newborn mortality is a lack of skilled health workers: in Somalia, which ranks fourth for neonatal mortality, there is only one doctor, nurse, or midwife for every 10,000 people. That would be like having about 50 medical professionals in the entire state of Wyoming.

How can these deaths be prevented?

The global community has seen success in reducing newborn deaths, and like the causes of maternal mortality, we know the solutions. Providing skilled care to mothers during pregnancy and after birth greatly contributes to child survival — especially hygenic care to prevent infections and care for infections with antibiotics. Low birth weight babies can be helped through skin-to-skin contact with the mother. We also must strengthen community support for mothers who do not deliver in health care facilities and help them recognize problems and how to access care in their area.

Even though newborn mortality rates are tied to income, great progress can be made even in low-income countries. One is example is Rwanda, where newborn mortality dropped by half from 1990 to 2016. The most important steps are improving the quality of care and increasing access to it.

What are the Sustainable Development Goals for newborn mortality?

The Sustainable Development Goal for newborn mortality aims to reduce global levels of newborn mortality to at least as low as 12 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030. In 2017, the global rate was 18 deaths per 1,000 live births.

If current trends hold, more than 60 countries will miss this target, and about half of them will not reach the target by 2050. These countries carried about 80% of the burden of neonatal deaths in 2016.

Under-Five Mortality

Incredible progress has been made to reduce levels of child mortality: since 1990, the global rate of child mortality has been cut by more than half.

Yet despite this progress, 5.4 million children died before their fifth birthday in 2017 — half of them in sub-Saharan Africa. Almost all of these deaths are due to causes that are understandable and preventable.

Where do these deaths occur?

Half of all deaths before age 5 happen in sub-Saharan Africa, and another 30% happen in Southern Asia. In sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in 13 children die before their fifth birthday, compared to just 1 in 185 in high-income countries. The worst countries for child mortality include Somalia, Chad, Central African Republic, and Sierra Leone.

What are the leading causes of child mortality?

Like maternal and neonatal deaths, most children under 5 die from preventable or treatable causes like complications during birth, pneumonia, diarrhea, neonatal sepsis, and malaria. The riskiest period is the first month of life, which is why reducing newborn mortality is a crucial step in reducing child mortality.

Almost half of all child deaths are linked to malnourishment, which makes children more susceptible to illnesses like diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria.

Why don’t these children have access to care?

Because newborn mortality plays such a crucial role in child mortality, many of the reasons are the same: care is often unavailable, inaccessible or unaffordable.

Income plays a major part in child mortality: Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 15 times more likely to die before the age of 5 than children in high-income countries. Even within countries, however, there are disparities. Child mortality rates in rural areas are 50% higher than children in urban areas. In addition, those born to uneducated mothers are more than twice as likely to die before turning 5 than those born to mothers with secondary or higher education.

How can these deaths be prevented?

Rates of under-5 mortality have declined faster than maternal and newborn mortality, partially due to the focus on reducing neonatal mortality rates. As we continue to improve newborn mortality rates, we will undoubtedly improve child mortality rates. Vaccines for diseases like measles, polio, diphtheria, and tetanus can play a crucial role in protecting children from dangerous illnesses.

What are the Sustainable Development Goals for newborn mortality?

The Sustainable Development Goal for child mortality is for all countries to reduce under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births.

So far, 118 countries have already met the target, and 26 countries are expected to meet it by 2030. More than 50 countries need to accelerate progress to meet the goal, however. If these countries did achieve the target, 10 million children could be saved.

How you can help

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work now and for the future at projecthope.org/donate.

Are you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.

Maternal Mortality

Maternal Mortality