Photos: The Journey Venezuela’s Mothers Endure

More than 6 million Venezuelans have migrated from their country due to years of humanitarian crisis. Among them are large numbers of pregnant women and mothers, many of whom have made the grueling trip alone. See how Project HOPE is providing care, and community, across the border in Colombia.

Yolanda knows where she’s going. What she doesn’t know is how she’ll get there.

Just days ago, the mother of three lost her own mom back home in Venezuela. Together with her 78-year-old father, who is blind, they buried her near their home. Then they gathered her three children, left everything behind them, and made a decision more than 6 million other Venezuelans made before them: they would leave home and migrate for good.

Since 2015, the mass migration of Venezuelans has been one of the largest displacement crises in the world. Some are fleeing violence; others, economic collapse or insecurity. For Yolanda, daily life had become untenable. Everything had become too expensive, from the food they ate to the clothes they wore. With her mother gone and no one able to care for her father, she was unable to work or provide for her kids. The only way to survive was to make the devastating choice to leave.

The vast majority of Venezuela’s migrants and refugees have relocated to other countries in Latin America or the Caribbean, including more than 2 million who are living in Colombia. The influx has strained Colombia’s local health systems, especially near the border in cities like Cúcuta. But for Yolanda, and so many others like her, that health care is absolutely essential, because in Venezuela it was either too expensive, insufficient, or nonexistent.

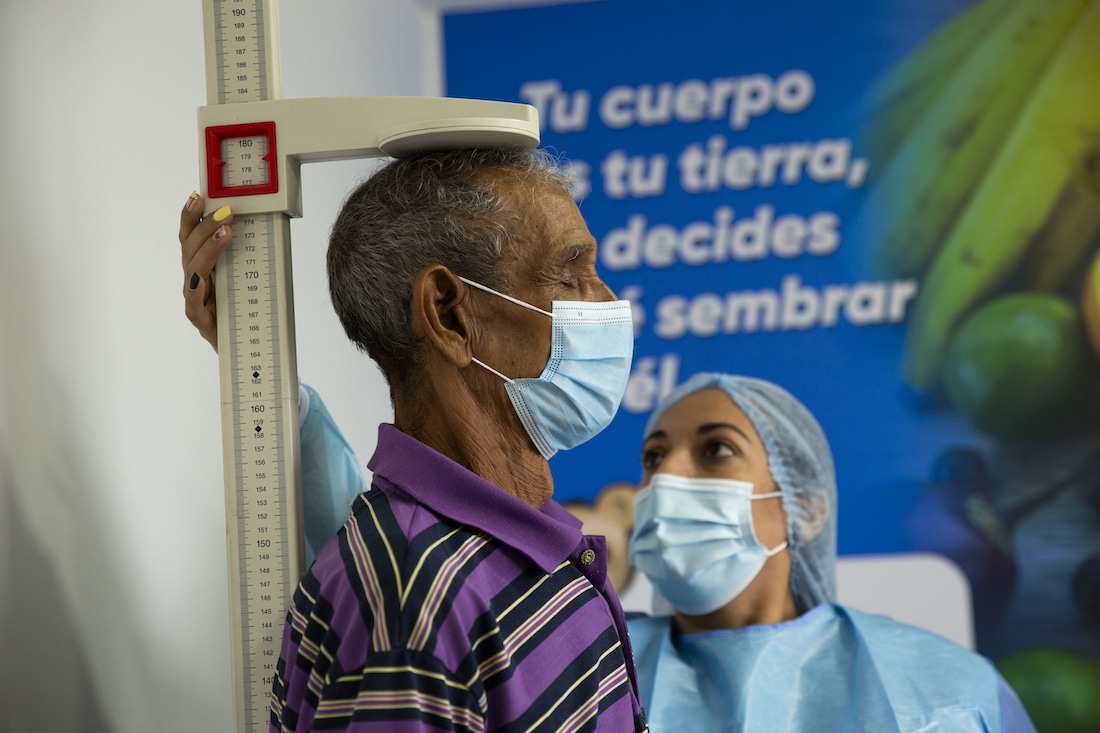

At a hospital supported by Project HOPE, Yolanda enters with her three children and elderly father, Carlos, for doctor visits after crossing the border. Their plan, she says, is to live with her sister in Cali. But Cali is 600 miles away, on the other side of Colombia, and an entire country of unknowns still lies before them.

Years of migration have pushed some of Colombia’s hospitals to the limit. The need is especially acute inside maternity wards, where many pregnant Venezuelan women arrive having gone months with no prenatal care. Some are as young as 14, and their high-risk pregnancies require extra attention from staff. Often, they have made the journey alone. Sexual violence is common among migrants, especially for women who take unofficial border crossings. Many of the women who cross the border come over for doctor visits or to deliver their babies in Cúcuta’s hospitals before returning back home to Venezuela. But some, like Yolanda, are migrating for good.

Project HOPE is working inside hospitals near the Colombia-Venezuela border to provide extra support to help health care workers meet the rise in need. Thanks to Project HOPE, Jorge Cristo Sahium Hospital has been able to hire multiple doctors, nurses, and gynecologists to provide essential maternal care for women before, during, and after delivery.

We’re also donating the crucial medical equipment these hospitals need. On a sunny October morning, a truck pulls up outside Jorge Cristo Sahium, and inside it are brand new radiant infant warmers, fetal dopplers, cribs, scissors, and other vital medical supplies. The delivery is a relief to the hospital and a lifeline to the women who depend on it.

Reaching pregnant women and mothers doesn’t just happen in hospital or clinic settings: it also means going where they are. In the small neighborhood of Villa del Rosario, not far from the Simon Bolivar Bridge, Project HOPE supports a local organization called Corporación Mujer, Denuncia y Muévete (Woman, Denounce and Move) that goes door-to-door to find Venezuelan women and bring them out of isolation to connect them to resources, care, and a community that will support them.

CMDYM brings Venezuelan women together in prenatal workshops to teach them essential knowledge as they go down the road of pregnancy and delivery, covering topics like diet, breathing, healthy lifestyles, and what to expect each trimester.

All of the women are Venezuelan, and many of them are as young as teenagers. For many of these women, being pregnant in Colombia is a difficult and lonely experience. In Colombia, CMDYM provides a community that helps them feel they’re not alone, in addition to providing the essential resources they need to stay safe and healthy while pregnant.

When the time comes to deliver their babies, many of the women will do it in a local hospital Project HOPE supports.

Erasmo Meoz University Hospital, in the heart of Cúcuta, is the city’s largest. The hospital provides comprehensive health care to Venezuelan migrants, including those who have crossed the border to have their children. About 80 percent of babies born here are to Venezuelan mothers—between 15 and 20 every day, or more than 5,000 a year.

Many of the babies are born premature, especially those born to adolescent mothers. Many of the women who come to deliver have other health conditions or diseases that require longer-term hospitalization, which Erasmo Meoz provides at no cost. Newborns are vaccinated and attended to by doctors regardless of their parents’ nationality or immigration status.

“We have been together with Project HOPE for many years now,” says Dr. Mario Galvis, a doctor at the hospital. “This hospital doesn’t discriminate. We don’t charge anything. We’re taking away the myth that Venezuelans are taking our resources.”

How you can help

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work now and for the future at projecthope.org/donate

Are you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.