We Are Project HOPE: Teresa Narvaez, Dominican Republic

Teresa Narvaez has spent more than 30 years helping save the lives of countless mothers and babies across Ecuador and the Dominican Republic.

Thirty-one years ago, Teresa Narvaez traveled 12 hours by bus from Quito to Cuenca, Ecuador, to interview for a job with Project HOPE.

“Something that I still hold very dear is that they got me a plane ticket to go back,” she says today. “It was a special flight because it wasn’t just any job — it was a job full of dreams and expectations of what was to come.”

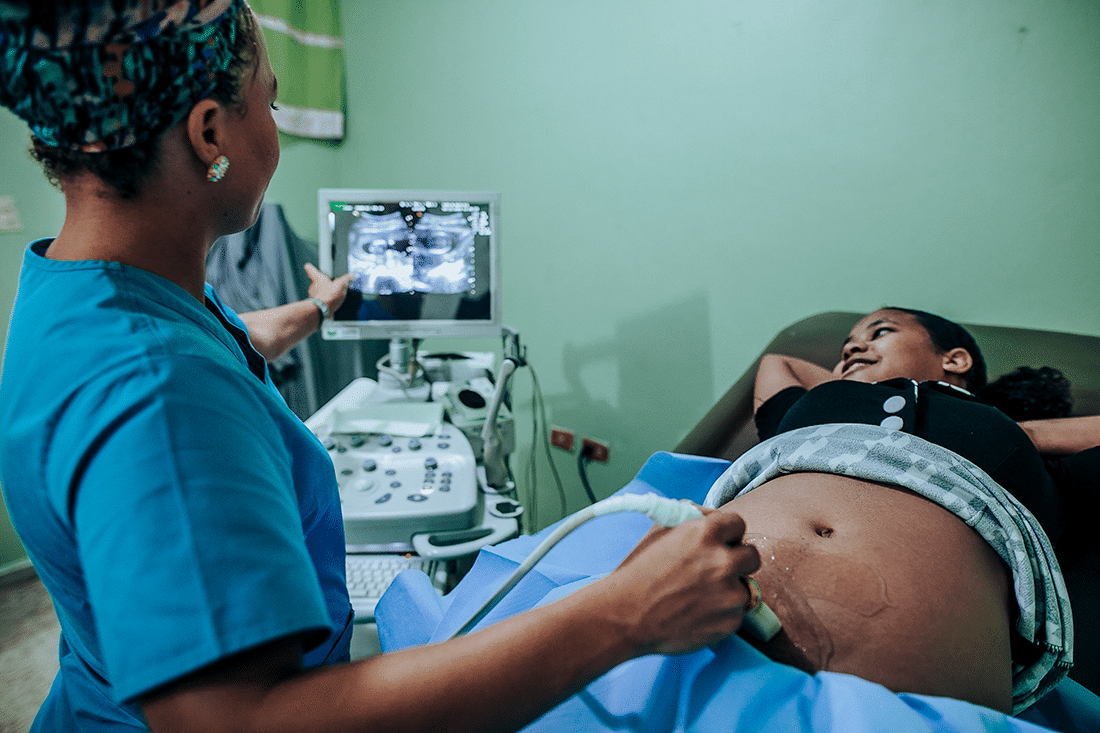

Three decades later, Narvaez is Project HOPE’s country director for the Dominican Republic, overseeing our work to protect maternal, newborn, and child health in a country with some of the highest mortality rates in the Americas region. That work has meant the difference between life or death for thousands of mothers and their babies, and has provided countless health care workers with the skills they need to reach their communities.

Read on to learn more about what keeps her going after 31 years, the challenges facing mothers in the Dominican Republic, and how Project HOPE is working to give newborns and infants a healthier start.

What is your background, and how did you come to Project HOPE?

I was born in Ecuador and raised in Tulcán, a city that borders Colombia. Then I moved to Quito to study to become a nurse. When I was about to graduate, I was one of three people selected to become part of an important large-scale investigation with the Ministry of Health.

The investigation was funded by USAID in order to uncover the socioeconomic factors that could contribute to mother and child health. As a field supervisor, I had to travel to every corner of the country. The ultimate goal was to develop a growth chart specific to Ecuador — to establish our own national standards that would allow us to understand what is expected of a mother and a child at any given age.

This research took place around 1986, and Project HOPE arrived in Ecuador by 1990. I started with Project HOPE in 1990 with a USAID-funded child survival program. For me, it was incredible — a big opportunity. I believe that Project HOPE saw in me a key person to be able to implement this program, not only because I knew the indicators and the context but because I also knew all of the geographic areas.

What was it like in those early days?

I can say that Project HOPE got to where others never did: whether it was by foot, car, motorcycle, horse, canoe, you name it — if Project HOPE had to use it, we did in order to reach the populations we needed to serve.

When we arrived in these communities we brought health care workers, medicines, vaccines, resources, whatever we needed to make sure we provided the health care that those populations or communities needed. Back then, not only were we providing a service, but we were also training local midwives and health promoters so they were able to identify risk signs and properly tend to mothers who would deliver in the community. All of this was because of how remote and inaccessible these communities were. So we had to make sure that they had the resources locally to tend to people when we were not there.

That child survival program was for five years, and when the program was closing down Project HOPE asked me to come to the Dominican Republic to implement the program here. I said yes. Initially it was for two years, to implement a primary care clinic under a sustainable model. And that was 26 years ago.

Does it feel like 26 years? Or has time just flown by?

Truthfully it has been a lot. But we have managed to do a lot as well. With our partners we were able to establish the first clinic at Herrera, an affordable clinic for an underserved population. It was deemed a success, and then they wanted a second one at Multi Plata, and it was also deemed a success, so we did a third one in Haina, and it was also well-received. Those clinics are still there as a legacy of our work.

Then we received guidance to pivot our approach from primary health care to tertiary care. Neonatal mortality is one of the main indicators that hasn’t changed, and that’s where we’re targeting our efforts now — the reduction of neonatal and maternal mortality that has remained stagnant for a good couple of decades in the country.

Read more: Improving the Odds for Women and Children in the Dominican Republic >>

Why do you think maternal and neonatal mortality rates have remained stagnant for so long?

It’s a contradiction, because you would think that a country with the economic indicators that the Dominican Republic has would do better when it comes to health care. But there are many factors that contribute to this stagnancy. For me, it was interesting because close to 100% of deliveries happen at the hospital, compared to other countries where they don’t have access or time to even drive to the hospital to deliver.

So we started paying attention to the causes. One is the low level of education that the population has. Many drop out of school before completing secondary school or sometimes even primary school. The other thing we’ve noticed is that we have very severe gaps in the proficiencies and skills of our health care workers — not necessarily because they don’t finish school but because of the quality of the education they’re receiving at universities. The third is the lack of resources — maybe the mother arrived at the hospital, and they had a skilled health care worker available, but they didn’t have the supplies they needed or the equipment to be able to provide the care that the mother or child needed.

How has Project HOPE been able to make a difference in these areas?

It is important to highlight that the clinics and the program have been recognized as a model that provided a training ground for nurses and doctors throughout the years. The clinics still serve as a hub to multiply the knowledge for those professionals to go and serve in other locations around the country. It was a great base for the implementation of community-based programs that we did throughout the years.

Now, more recently, our programs’ main focus is the training of health care workers to improve their skills at the tertiary level, working specifically with neonatologists and OBGYNs. A very special program that we helped implement was a nursing education program that was directed to improving the skills of nurses to tend to mothers and newborn babies at the primary and secondary level of care.

But there’s still a lack of comprehensive health care despite everything that we’re doing. There are gaps in the referral process — that means when you have a mother who should go from the primary level of care to the second or third level to deliver their babies, how they receive follow-up and return back for the regular health care at the primary level is still lacking, and we still strive to continue developing the quality of the health care worker.

How did COVID-19 impact the health of mothers and babies?

The services normally available to them were compromised throughout 2020. Unfortunately, that decrease in access to health care translated to an increase in maternal and child deaths for the year. All of the improvements that we’ve managed to accomplish up until 2019, which were leading to a downward trend in indicators, could not be sustained for 2020 because all of the manpower and resources went toward addressing the COVID-19 emergency.

Measures that were in place due to COVID-19 prevention efforts became limiting factors for us in the sense that we couldn’t do the trainings we were meant to do, because they have to be face-to-face and involve hands-on practice. Also, many of our health workers were sent home because of personal health factors that put them at higher risk. We were left without 60% of the health workforce because of that — some of our best OBGYNs, neonatologists, and nurses were told to stay home because we couldn’t risk losing them to COVID.

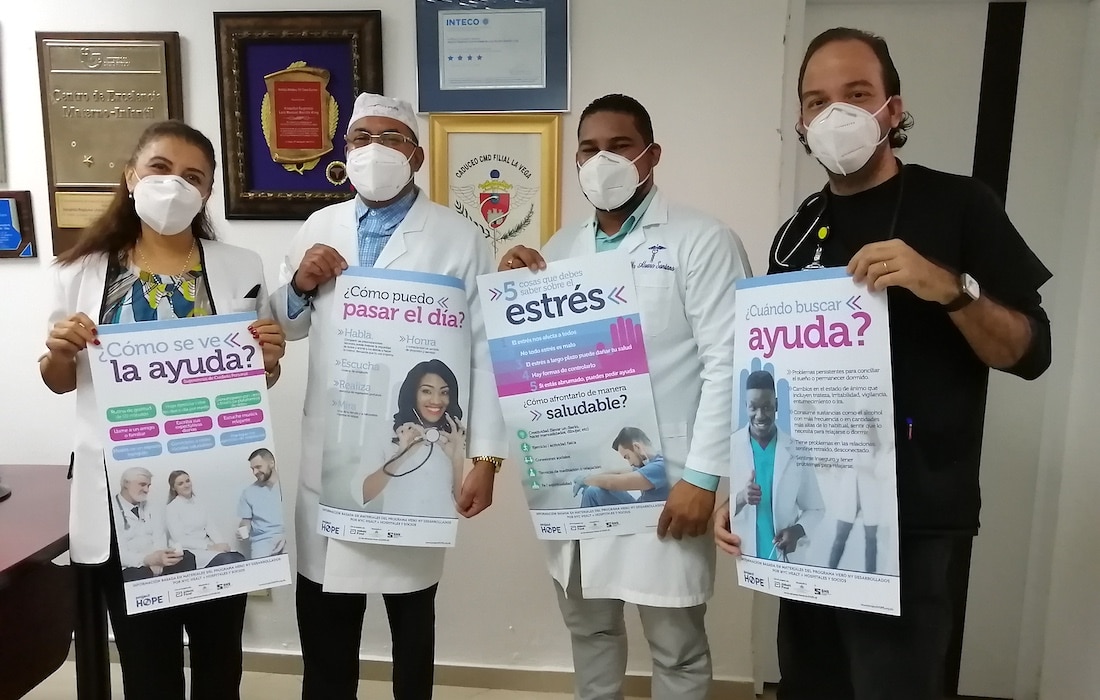

Even though local progress was hindered, we still feel we accomplished a lot with our virtual COVID-19 trainings. Being part of Project HOPE’s regional effort to train health care workers in 17 countries throughout Latin America allowed us to increase our impact beyond our own borders.

What led you to want to devote your life to working in global health?

When I was in high school, I did my graduate thesis on the cycle of human life, following it step by step — the evolution of pregnancy, childbirth, the development of the child, the adolescent, the adult, through old age. The most important thing about this research was that we were able to observe the delivery care live. That moment changed my life. Beyond obtaining a grade, I discovered I wanted to be a doctor or a nurse to help mothers in that special moment — to be vigilant of the health of the mother and the baby.

Are you still a registered nurse? Do you ever provide hands-on care for mothers and babies and still lead trainings yourself?

Yes, I’m still a registered nurse. Now I’m getting my MBA. Bigger than my role as a country director for Project HOPE is my technical expertise that has come in handy to be able to train and guide health care workers throughout these years — not only training nurses and doctors at the clinics, but also being a supervisor and making sure I address and identify possible situations when it comes to delivering babies and other health care emergencies. I’ve been there, not doing it myself, but being the observant eye and I’m able to correct or guide when a nurse or other health professional is attending or tending to mothers.

It’s been over three decades since you started working at Project HOPE. What motivates you and keeps you going after all this time?

It is immensely gratifying and wonderful to be able to say that my professional life has been entirely dedicated to the health and well-being of people — particularly mothers and children. What motivates me is seeing the birth of healthy children and mothers committed to giving them the best lives they can.

But I’d like to close with two experiences that I’ve had at Project HOPE. The first was back in 2018, when I had the opportunity to visit my home city of Tulcán, Ecuador, right after returning from Guatemala for an emergency response to the volcanic eruption. We were there to help mothers and babies, but I was surprised to find a more dramatic and painful situation in Tulcán with the migrants coming from Colombia after crossing the border from Venezuela — many of them without anything to eat, many of them who had been walking for days. It was a tragedy that impacted me way more than what I had just seen during the emergency response. I called Project HOPE right away and they gave me the opportunity to go and make an assessment, and thanks to that assessment we can now see a very positive program being implemented to help Venezuelans crossing to Colombia.

And the last thing I would like to highlight is Cuenca, the place I first started out with Project HOPE, which I can now proudly say is the hub for a new program in Ecuador. I was part of those initial discussions with Project HOPE, and I’m glad to say that despite being in the Dominican Republic for the past 26 years, Project HOPE has continued to provide me opportunities to help and make contributions elsewhere — especially back in my home country, Ecuador. We now have a country office again in Ecuador and they just started a fantastic program, coincidentally in the very city where I first started out.

How you can help

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work now and for the future at projecthope.org/donate

Are you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.