COVID-19 Devastated New York’s Health Workers. Their Experience Is Helping Others Around The World.

With support from the Abbott Fund, Project HOPE is piloting a new program to provide mental health and resiliency tools for health care workers on the front lines of COVID-19.

The story of a disease is told in numbers: case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths. Numbers help us make sense of where a disease has spread and forecast where it might be heading; they reveal who is most at risk, and what solutions might protect them.

At COVID-19’s peak in New York City, the numbers told a story of profound challenges, with more than 5,000 people contracting the virus every day and overwhelmed hospitals pushing a health system to its brink. Inside the hospitals where the battle was fought, however, the virus exacted a toll that was tougher to track. Shift after grueling shift, COVID-19 strained the mental health of New York City’s doctors, nurses, and health workers.

It’s a cost being borne around the world: Over 570,000 health care workers have been infected with COVID-19 worldwide. But millions more face a burden that’s harder to diagnose — an extreme toll on their mental health, compounded by the increased dangers of their job and the risks they face day after day.

Thousands of miles from New York, however, the pandemic’s devastation is now providing a lifeline of hope, thanks to a new mental health program Project HOPE is piloting in Indonesia.

With support from the Abbott Fund — the foundation of the global health care company Abbott — Project HOPE is working with local partners to pilot a new program to provide mental health and resiliency tools for health care workers. Held in-person and online, the trainings cover topics like stress, grief, and trauma — subjects many health care workers have never had the chance to discuss openly.

“The relationship between mental health and well-being is directly proportionate,” says Rawan Hamadeh, Project HOPE’s associate project coordinator for mental health programming. “Mental illness, especially depression, increases the risk for many types of physical health problems, particularly long-lasting conditions like stroke, Type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. In developing countries, however, mental health is neglected for many reasons, including high stigmatization, a lack of resources, low levels of knowledge, and the prioritization of other health issues.”

“Mental illness, especially depression, increases the risk for many types of physical health problems, particularly long-lasting conditions like stroke, Type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.”

The trainings are adapted from HERO-NY, a program developed by New York City Health + Hospitals in partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense, and include five sessions:

- Stress, Trauma, and Resiliency

- Personal and Professional Wellness

- Impact, Effect, and Outcome on Frontline Workers

- Seeking Help for Ourselves and Others

- Resilience and Wellness Program Development

The first session was held in Indonesia in September and was implemented by KUN Humanity System+, a local health and humanitarian organization with experience handling mental health issues for health workers. Doctors, nurses, and psychologists were invited to attend, with all the sessions translated into Bahasa Indonesia.

Together, more than 130 attendees discussed burnout, exhaustion, and compassion fatigue. They learned coping strategies and techniques for self-care. But more importantly, they did it openly — an important first step to normalize a support system that is too often overlooked in clinical settings.

“Trainings like these can be a doorway to decrease stigmas and increase knowledge around mental health, which is the building block of mental health awareness and eventually better mental health service delivery,” Hamadeh says.

A Hidden Crisis

The world’s health care workers have never been under more strain. A survey of 1,200 Chinese health care workers who treated COVID-19 found that 70% reported psychological distress and half had symptoms of depression. It’s not a topic often discussed in hospitals and clinics — stigmas about mental health persist among health care workers, which can prevent them from asking for help.

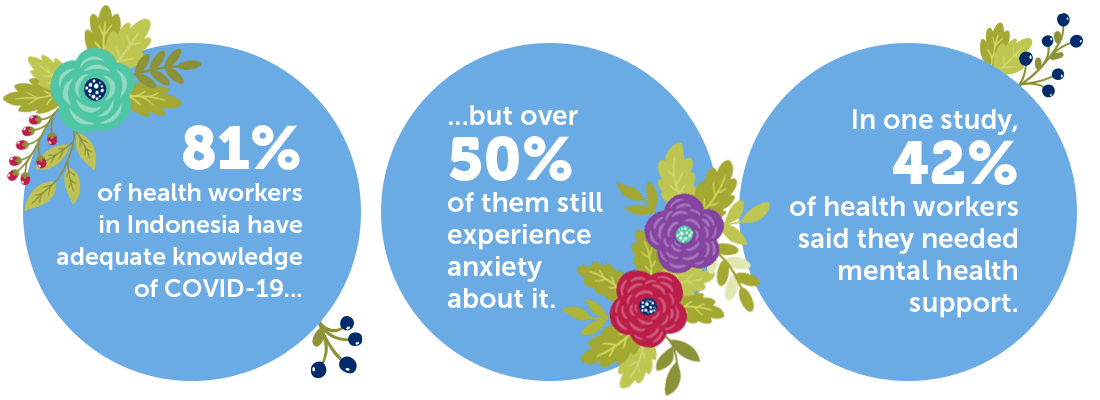

In Indonesia, researchers have found that health workers who treat COVID-19 patients are nearly two times more likely to experience symptoms of depression than other health workers. Though 81% of health workers have adequate knowledge about COVID-19, meanwhile, more than half of them still experience anxiety about it.

The reasons for that anxiety are long: from unsafe work environments, to a lack of protection, to the fear of being discriminated against if they contract the virus. Some doctors and nurses say they feel it was unfair that they were transferred to high-risk COVID-19 units. Others can’t sleep or worry about passing the virus to their families.

In one Indonesian study, as many as 42% of respondents said they needed mental health support.

“Most health care workers in Indonesia do not have the experience to deal with long-term crisis situations like this,” says Yogi Mahendra, Project HOPE’s emergency response specialist for Southeast Asia. “What often happens is health workers feel anxiety due to work pressures, including excessive work hours, internal conflicts, and more. When you couple that with high expectations from patients and family — especially when a situation does not go well — it will be a burden that will be carried for a long time.”

“Most health care workers in Indonesia do not have the experience to deal with long-term crisis situations like this.”

That lack of support is likely to compound the problems COVID-19 has revealed. There is a major shortage of health care workers worldwide, a problem that will only get worse as workers get burned out or leave for other fields. The pandemic has also highlighted the inequities within our health care systems, with marginalized communities bearing the outsize costs of the virus.

In countries where basic medical equipment or protective gear is short, quality mental health support is often an afterthought. Unfortunately, those very places are often where mental health support is needed most — where conflict has devastated health systems, or where humanitarian crises have endured.

In Indonesia, Mahendra says, the program aims to build on the existing system for mental health support that tends to focus more on medical care rather than psychological consultations. To help close that gap, certified psychologists were on-hand at Project HOPE’s first two-day training, so each of the 132 participants could schedule private dialogues, counseling, or ongoing discussions for up to a week after the training was over.

For many of them, it may have been the first time they were able to discuss their own mental health with a professional.

“We wanted participants to better understand the material and get to know their own mental health better before helping others,” Mahendra says.

A Scalable Solution

Project HOPE is following the Indonesia training with sessions in the Dominican Republic, which has had more COVID-19 cases than anywhere else in the Caribbean. Eventually, the goal is to expand the program around the world, using a training-of-trainers model similar to Project HOPE’s COVID-19 training sessions that have reached almost 80,000 health care workers worldwide.

That support will better help the world’s health care workers look after their own mental health during the pandemic, but also for the unforeseen events to come. Hamadeh, who is Lebanese, traveled to Beirut shortly after the devastating Port of Beirut explosion in August, where years of economic crisis and an overstretched health system left the population unprepared for the trauma of a crisis that killed over 200 people and left 300,000 homeless.

“Months after the explosion, people are still having nightmares, people have become paranoid whenever they hear loud noises, they are having flashbacks, and they are experiencing PTSD symptoms without knowing what they are and what they should do about them,” she says. “There’s a very high need for mental health support at this time in Lebanon because of the increased risk of developing mental health issues, as well as the lack of actual services to provide support to those who are the most vulnerable.”

The immediate needs after a crisis like that often focus on emergency medical support, Hamadeh says. But the internal scars will linger, too. And connecting people to the care they need — in Lebanon, Indonesia, the Dominican Republic, and beyond — starts by helping those on the front lines find the support they need to look after themselves.

“I think it is extremely important for people to deal with mental health illnesses just as they would any other type of illness,” she says. “There is no health without mental health. Let’s talk and learn more about mental health issues. Let’s normalize them. This way we can help people seek the appropriate care and save their lives.”

How you can help

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work now and for the future at projecthope.org/donate

Are you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.