The 5,000-Mile Journey

Amid pandemic fallout, climate change, and growing instability, growing numbers of migrants are risking their lives on the northward journey to reach the United States. Project HOPE is working closely with local partners to provide care along the way.

Carina knew it was time to leave home when her family started going hungry.

Just 20, she and her twin boys recently migrated to Colombia from Isla de Margarita, an island off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. Together, they traveled by boat, foot, train, and strangers’ trucks to make it to Cúcuta, Colombia, where they reunited with her husband who came first to find work. She is seven months pregnant.

Carina’s family is trying to start a new life in the small community of Villa del Rosario, near the Simon Bolivar Bridge that links Colombia to Venezuela. They share a single room in a warehouse with several other migrant families.

The conditions may seem dire, but here they see the promise of a life they could not build in Venezuela, and access to services they did not have—like basic health care.

“We didn’t have enough money for food and other necessities,” she says.

Amid skyrocketing inflation, political instability, and sometimes violence, more and more Venezuelans are braving the journey to other countries, including the United States, and Project HOPE is working closely with local partners to support them along the way.

Venezuelans are among the fastest-growing populations entering the U.S. through Mexico, making a perilous journey north in search of safety, stability, and better opportunity. The number of migrants arriving at the southern border of the United States has skyrocketed since 2021. Between 2015 and 2018—the height of Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis—fewer than 100 Venezuelan migrants were apprehended at the border each year. In 2022, more than 150,000 Venezuelans arrived at the U.S. border. It was almost four times the number of migrants that arrived just one year before.

It is an extremely dangerous journey for girls and women who travel alone, even those who only cross to Colombia. For those who are pregnant, even arriving at your destination and finding a place to stay can be a lonely, isolating, difficult, and solitary experience.

Shortly after arriving in Colombia, Carina found prenatal care and a community of other pregnant women through a local organization called Corporación Mujer, Denuncia y Muévete (CMDYM, or Woman, Denounce and Move). With support from Project HOPE, CMDYM brings Venezuelan women together in prenatal workshops to teach them essential health knowledge, like prenatal nutrition and mental health. All of the participants are Venezuelan, and some are as young as 14.

CMDYM has provided Carina with a community so she feels less alone, in addition to the resources she needs to stay safe and healthy during her last few months of pregnancy. When the time comes to deliver her baby, she will go to the local hospital, which Project HOPE supports.

Continuing a perilous trek

Carina and her family are planning to stay in Cúcuta, but for many Venezuelans, like Yolanda, this trip is only the first step in a journey of thousands of miles.

Yolanda, 28, wants to travel 600 miles through Colombia, from Cúcuta to Cali, where her sister lives. But she doesn’t have money to get there, and she can’t find work.

Yolanda isn’t traveling alone—she’s with her three young children and her 78-year-old father, Carlos, who is blind. They left their home in Aragua, Venezuela just a few days ago, after her mother died. Now, they’re living at a hotel near the border until they have enough money to buy bus tickets and continue on their journey.

“The main problem we faced in Venezuela was that we didn’t have enough food,” she says. “We were starving. We didn’t have clothes. We were completely alone and didn’t have any help. Even if you have money, you can’t buy things because things are very expensive.”

When Yolanda’s family crossed the border into Colombia, one of their first stops was a hospital where Project HOPE provides urgent health care. For Yolanda, and so many others like her, this free health care has been absolutely essential because in Venezuela it was either too expensive, insufficient, or nonexistent.

Years of migration have pushed some of Colombia’s hospitals to the limit. The need is especially acute inside maternity wards where many pregnant Venezuelan women arrive having gone months with no prenatal care.

Project HOPE has helped hospitals near the Colombia-Venezuela border meet the rise in need by providing health care workers, equipment, and essential medical supplies like radiant infant warmers, fetal dopplers, and cribs.

“The main mental health cases we see are from women who experienced violence or violations. When they come here, they see the psychologist first, then the nutritionist, and then the general practitioner.”

“They arrive with many diseases—problems with their stomach, problems with their skin—but our main focus is on maternal health,” says Karen, the nurse who cared for Yolanda’s family. Karen, who was hired by Project HOPE, says the vast majority of her patients are Venezuelan.

Sexual violence is common among migrants, especially for women who take unofficial border crossings or travel alone. Some migrant women report taking contraceptives before starting the journey northward to prevent pregnancy in case of rape or sexual trafficking.

In addition to the physical needs, the mental health needs are great. “The main mental health cases we see are from women who experienced violence or violations,” Karen says. “When they come here, they see the psychologist first, then the nutritionist, and then the general practitioner.”

More than 7.1 million Venezuelans like Carina and Yolanda have fled the political, social, and economic turmoil in their home country since 2015, mostly for nearby countries like Colombia and Ecuador. But more and more families are attempting the 5,000-mile journey to the U.S.

To get there, they must traverse one of the most treacherous wildernesses on the planet—a 66-mile stretch of jungle terrain connecting South and Central America called the Darién Gap. Between 2010 and 2020, fewer than 11,000 people on average dared to cross the Darién Gap each year. In 2022, nearly 250,000 migrants braved the gap, most of them Venezuelan. Not everyone makes it through: 36 deaths were reported last year, and the number is likely much higher.

For those who do survive the journey, the challenges don’t end, they just change—and health care remains difficult to find.

Finding safe shelter on the move

In Mexico, migrant families arriving to shelters are past the brink of exhaustion. Children suffer most. They often arrive malnourished and dehydrated because of a lack of food and clean water.

“Migrants don’t want to seek medical care in primary health centers unless there is an emergency,” says Chessa Latifi, Project HOPE’s Senior Program Advisor for Humanitarian Response and the Latin America/Caribbean Region. “They worry that stopping for help might make them lose their guide or group or be identified and reported to the Mexican government.”

Most shelters are full and operating beyond capacity, and many migrants sleep on the street.

Project HOPE recently completed an assessment on health; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); and protection needs in shelters along migrant routes in Mexico. Borders cities such as Nuevo Laredo, Ciudad Acuña, and Piedras Negras do not have the capacity or support to respond to the migration situation. In Ciudad Acuña, shelters have been closed to prevent people coming.

At many of the shelters Project HOPE visited, there was a shortage of medicines and basic cleaning supplies. Top morbidities are skin injuries, gastrointestinal disease, and respiratory tract infections. We found mental health services to be either scarce or nonexistent.

“The primary health care and mental health care needs to manage the impact of such a traumatic journey remain underserved for migrants,” Latifi says. “A person only chooses to make the journey north out of desperation and lack of any better option.”

Read our full Migrant Needs Assessment from Mexico >>

In the U.S., the challenges don’t end

In Texas, finding medical attention without health insurance or money is one of the more stressful endeavors for families who make it across the border—especially during a global pandemic.

Through a program funded by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, Project HOPE is improving access to COVID-19 vaccines through a coalition of free and charitable clinics in Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.

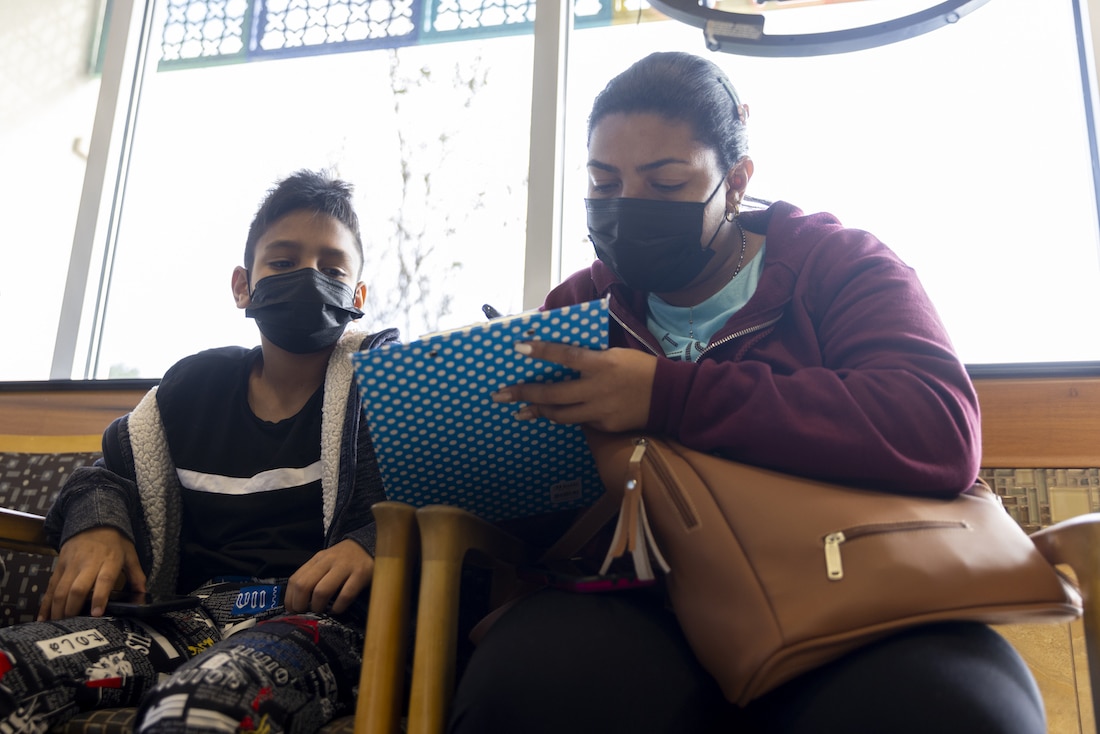

These clinics have served tens of thousands of refugees, migrants, and undocumented and uninsured populations, including Mariel and her 11-year-old son, Vicente.

It took Mariel and Vicente 15 days to travel from Venezuela to Houston. Vicente contracted COVID-19 while staying at a shelter on the border and was quarantined with a high fever for 11 days.

Mariel says the hardest part of their journey was the lack of food and being in shelters.

“My child didn’t go to the bathroom for six days and didn’t eat for two days,” she says.

Now set up in their new home in Houston, they have begun the immigration process. Vicente is fully recovered and ready to begin school. Mariel brought him to Ibn Sina Clinic for his first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, one of the free safety-net clinics Project HOPE supports. She didn’t fully trust the vaccine back in Venezuela, she says, nor was it available, but she does now thanks to a community health worker named Aftab who educated her about the vaccine.

“I’m more comfortable now,” Mariel says. “I can send him to school and know he is protected.”

A life of new challenges

Farther north, in Washington D.C., the struggles for migrant families are still far from over.

After weeks and months of being on the move, they’ve finally arrived in a new city, in a new country, perhaps even at their final destination, only to face a daunting new challenge: starting over in a new home without any support. The list of needs is long and critical: food, housing, work, and quality health care. There are visa and work permit challenges, language and cultural barriers, and a lack of connections and resources.

In September 2022, Washington, D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser declared a public health emergency in response to the growing numbers of migrants being bused to the nation’s capital from Texas and Arizona. Migrants have been dropped off in multiple locations around the city at all times of day with little to no information or support.

“Our center is just a step in their pathway. Many of the migrants come through on their way to New York. Many are ready to continue their journey that same day.”

Project HOPE partnered with SAMU, an international humanitarian nonprofit, to support asylum seekers as they arrived in Washington, D.C. In addition to providing SAMU with technical support to continue growing their operations, we donated a 16-passenger van to help provide transportation for families when they first stepped off buses—a critical lifeline to ensure they were safely and humanely transported to shelters where they could access care and resources. We also helped the organization purchase essential items like food, bedding, and laundry services, and trained SAMU staff in psychological first-aid to help address migrants’ mental health needs as they cope with the stress of the traumatic journey they endured.

“Our center is just a step in their pathway,” says Juan Gonzalez de Escalada Alvarez, Chairman of the Board at SAMU. “Many of the migrants come through on their way to New York. Many are ready to continue their journey that same day.”

They’ve journeyed across many borders and thousands of miles, carrying a mix of desperation and hope that keeps them going—hope for safety, security, opportunity, and the chance to build a better life for their families.

Back in Cúcuta, that chance starts with a bus ticket. Yolanda and her family hang in the in-between, holding on to their hope for a new life in Cali, waiting for the money they need to continue on. For her children and her father, Yolanda dreams of one thing: stability.

“When we arrive in Cali, we can get help from my sister,” she says. “I want to get a new job. I want my kids to get an education. But mainly I want someone who can take care of my father. He doesn’t have anyone who can care for him. I want a more stable situation.”

How you can help

Make a lifesaving gift to support our work now and for the future at projecthope.org/donateAre you a health-care or other professional who would like to learn more about volunteering abroad with Project HOPE? Learn more about our volunteer program and join our volunteer roster.

Stay up-to-date on this story and our lifesaving work around the world by following us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, and help spread the word by sharing stories that move and inspire you.