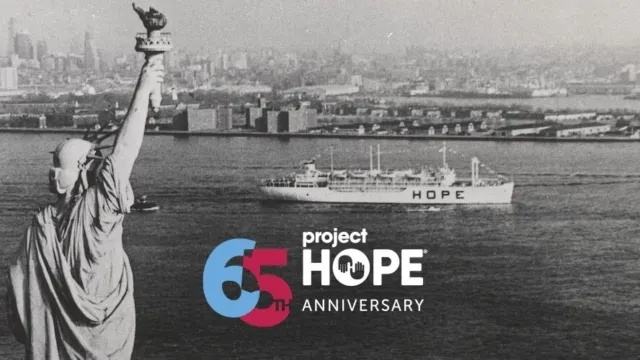

Celebrating 65 Years of HOPE

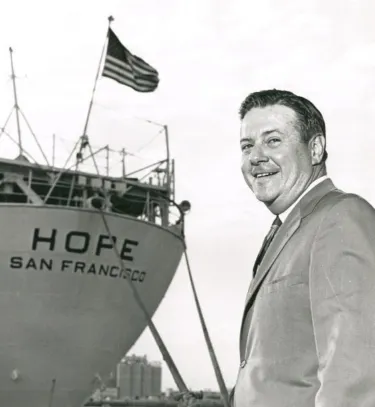

In 1958, Dr. William B. Walsh had an idea: a world-class hospital ship that could deliver essential health care around the world. This month, we celebrate 65 years of HOPE and a legacy that has grown to reach millions of people every year.

Project HOPE started with an idea. Dr. William B. Walsh — cardiologist to President Eisenhower — pitched the president on a floating hospital ship that could sail the world training local health workers and delivering world-class care. In December 1958, Project HOPE was born.

Chartered for $1 a year from the U.S. Navy, the SS HOPE made 11 voyages over 14 years to every region of the world, delivering health care, training health workers, and strengthening health systems.

Though the SS HOPE was retired in 1974, our global team has continued to carry the spirit of the ship ever since. Every day, we’re expanding equitable access to health care by equipping local health workers in over 25 countries to care for their communities and respond to urgent health crises. Thanks to Dr. Walsh’s vision, Project HOPE has grown to reach millions of people every year while responding to the world’s most urgent health crises in Ukraine, Sudan, Haiti, and around the world.

To celebrate our 65th anniversary, we asked a few of our alumni (affectionately known as “Hopies”) to share some of their memories and reflections from decades past. Here are their stories.

Dave Reiser

SS HOPE and Navy Mission

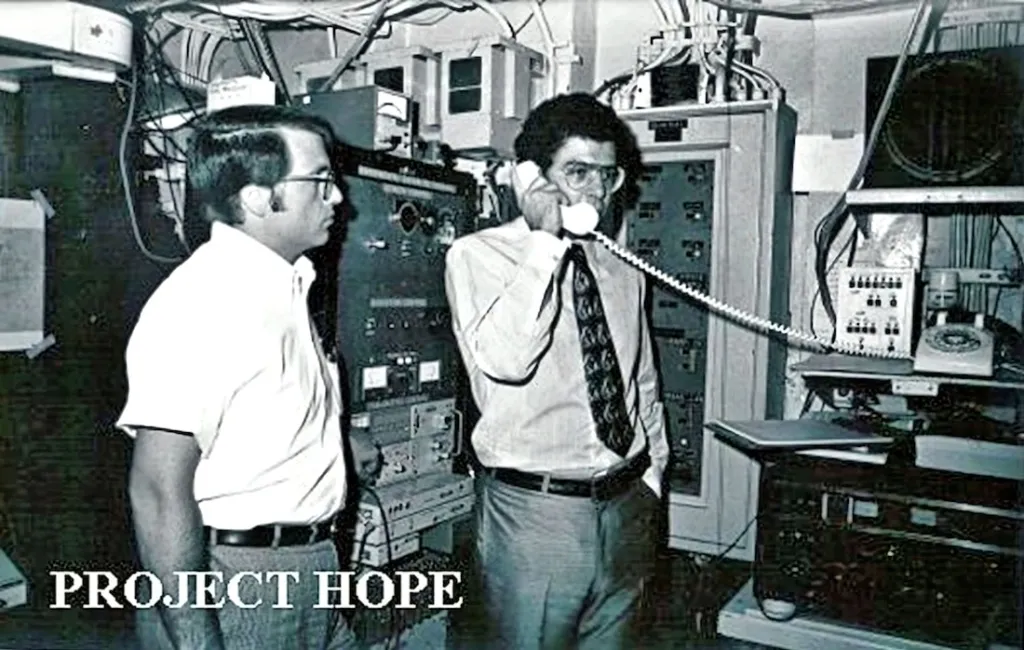

The year was 1973. I was a bench tech at COMSAT Labs then, still trying to finish my degree in electronics. Just before Christmas of that year, my boss, Kim Kaiser, called and asked if I would like to go with him on the SS HOPE to Brazil to install and operate the first NGO satellite terminal on an ocean-going ship — a milestone in satellite communications. Having served in the Navy, I jumped at the opportunity to go back to sea. It’s a project that has influenced my life ever since.

Up to this point, communications to and from the ship had been handled by amateur radio operators, which was hit or miss at times due to atmospheric conditions. The satellite communications were near perfect all the time, and little did we know that we were making telecommunications history.

I felt fortunate that I got to meet the most fantastic people in the world: Project HOPE volunteers. It’s been 50 years since that time, and I still remember the nurses who gave up a year of their career to care for children with terribly bowed legs, children with facial tumors, and one child who drank lye and destroyed her esophagus. I can imagine that those nurses had never seen such terrible, debilitating conditions. There was one lady who was a silver-haired nurse and grandmother. I never knew why she joined the project at her age. Funny, now I think I would do the same thing.

Then there was the permanent staff who also had an incredible dedication to their jobs. There were senior staff members who made Project HOPE their life’s work.

I was envious of all these people. They gave so much of themselves, and what they got back was priceless. I remember the smile of that girl with the bowed legs. She could stand up straight now. The child with the facial tumor was holding up his thumb saying “tudo bem” (all good).

In 2008, I was able to help Project HOPE again when I was asked to repeat the satellite experiment we did in 1973, but this time on the United States Naval Ship Mercy in honor of HOPE’s 50th anniversary. “You bet I would,” I said, though I no longer worked for COMSAT. I took leave from my job, packed my bags, borrowed a portable satellite terminal, and told my loving wife I would be back in three to four weeks.

I met the Mercy in Singapore, and a new adventure began. We sailed on to Dili, in Timor-Leste; Darwin, in Australia; and Port Moresby, in Papua New Guinea. I met yet another group of wonderful people, some from Project HOPE, some in the U.S. Navy, and others in the U.S. Public Health Service. All of these people went off for weeks or months and dedicated their time and efforts for the benefit of others. Sure, some were paid, but to do this work continuously takes dedication to the task and a willingness to leave their jobs and families. I salute you all and thank you for your service.

Being around these wonderful Project HOPE people has had a positive influence on my life. My wife and I now live in a retirement community. Our population is almost 1,000 residents, and half have limited knowledge of computers. I have made it known that I will help anyone at no charge. I also offer help with cable TV and telephones. I get calls from residents telling me they can’t turn their computer on, or they have lost internet, or they need help connecting their printer. When they offer to pay me, I say, “Thank you, but no. I’m happy to help.” I want to give back to others as I saw so many volunteers do during my time with Project HOPE. Thank you, Hopies!

Did you know?

The SS HOPE had its own machine on board that converted distilled seawater to milk. Using blended powdered milk and fats, the “Iron Cow” could produce 1,000 gallons of milk a day while at sea.

Carolyn Kruger, PhD

Project HOPE volunteer, former nursing director

From 1991 to 1996, after the fall of communism, I supported the establishment of Project HOPE’s Nursing Centers of Excellence in Eastern Europe.

As early as 1974, Project HOPE had a partnership with Boston Children’s Hospital and the Polish-American Children’s Hospital in Krakow, a tertiary care center for southern Poland. After the fall of communism, Project HOPE assessment teams discovered that the hospital’s patient care was very outdated and decided to develop Nursing Centers of Excellence as exemplary, state-of-the-art centers to help improve the quality of care. The concept included choosing an existing tertiary site to be a model of care for other hospitals in the country, demonstrating the application of concepts in pediatric nursing, including patient-centered management and collaborative multidisciplinary team approaches. The Centers benefitted from technical support from Project HOPE teams, which included education and training in all areas of care, with an emphasis on neonatal intensive and pediatric cardiovascular care.

The first Center was established at the Polish Children’s Hospital in Krakow, and from this “hub” other Centers were established at children’s hospitals in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The interest in these Centers spread to other countries as well, including Romania and Armenia.

I was Director of Nursing at Project HOPE Millwood during this period of time, and it was wonderful to work with the nurses in the Centers to improve the quality of care for children and their families. Many of the professional relationships between these nurses and the Project HOPE U.S. nurses lasted many years — some to this day — and the Centers have continued to grow in their capacity to provide care.

I see the Centers as an example of Project HOPE’s legacy of assistance to countries during critical times, and our commitment to long-term support in order to sustain the capacity of countries to help themselves in recovering from disasters or political turmoil. The Centers were very successful thanks to the eagerness of local health providers in the Eastern European countries to improve their health care delivery systems and train their health workers. Also key to the success was our deployment of long-term nursing consultants to each Center, who worked alongside local nursing staff for many months, up to a year.

Did you know?

The 1961 documentary film Project HOPE documented the maiden voyage of the SS HOPE and won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject at the 34th Academy Awards.

Joanne Jene, MD

SS HOPE and land

I served eight missions as an anesthesiologist, four of them on the SS HOPE.

The opportunity to treat, teach, and be a team member of Project HOPE has been the most awesome memory of my life. I’m proud to be an alumni of Project HOPE. It’s an honor to consider myself a “Hopie.” And it’s a blessing for Dr. Walsh to have the People-to-People concept for all to follow as a guide for the future, as we move into the challenges of the AI century.

Dr. Tom Kenyon

Land and HQ; CEO 2015-2019

I was doing my pediatric residency in 1984. I was sitting in the ward one day when my residency director, who had been with Project HOPE in Brazil, tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Do you want to go to Grenada? Project HOPE is trying to find pediatricians to volunteer after the war.” I went for two months and then returned to the states to finish my residency.

About 10 months later, Project HOPE called looking for a full-time pediatrician to go back to Grenada and develop a program. That’s when I joined — in 1985. I went back for two years, and I was the only pediatrician on the island. I was also responsible for reactivating nurse practitioners who had gone dormant under the Cuban health system. We activated a network of clinics, where these nurse practitioners were based, and we developed a manual of pediatric protocols and guidelines to help train them on treating common ailments.

We had a huge problem with anemia. It was a frequent occurrence for a mother to bring her child to the clinic and complain they weren’t talking, that they were tired and inactive. We’d check their blood and find profoundly severe anemia in these children, because of parasites. But we needed to know which parasite in order to administer the right treatment. I didn’t have a laboratory, but I learned how to do a stool parasite test. But you need a solvent, and all I had was gasoline. So I was driving around to the clinics with bottles of gasoline in my backseat. The nurse practitioners learned how to use a hemoglobinometer and look at it using a flashlight battery to read hemoglobin levels. If it weren’t for this intervention, these children would have gone through life without developing psychosocially.

Some years ago, I heard that the program had stopped running because no one had the money to buy the battery that operates the hemoglobinometer. This taught me that you really have to think through how to make programs sustainable for the long run. It also taught me Project HOPE’s prioritization of the counterpart. This is a philosophy that Project HOPE and “Hopies” had on the ship — the ship would team up with the local hospital, the surgeons would team up with the surgeons, the nurses would team up with the nurses, and they would transfer knowledge and skills that way. The reason we work anywhere is to develop counterparts to assume responsibility for their health care system and make the changes they believe they need to make — not for us to operate it or to change it. We’re not working to impose our vision. So, in this case, anemia was extremely important to these nurses because they saw it all the time, and we built their capacity to respond to it and treat it.

In 1987, I became the first country director for southern Africa, in Swaziland, and was focused on responding to the AIDS epidemic. I left Project HOPE in 1992 to pursue public health training. Two years later, in 1994, I joined the CDC as a medical epidemiologist and played several roles in country programs and senior management over 21 years.

In 2015, I decided to leave government and return to Project HOPE as CEO. My focus has been on strengthening our global public health programs, attracting the right people with the right skillsets, and expanding our geographic and programmatic reach. I’ve learned that it all boils down to the staff we recruit. You have to be successful to attract good people. And we’ve really attracted some good people, so that tells me we’re being successful. Our people are our most important asset and the key to success.

I’ll be retiring at the end of this year. I feel really enthusiastic about where Project HOPE is now and where it’s headed. I think everything is clicking on all cylinders, across the board. We have excellent people. I feel very positive about where the organization is — I don’t think I’d feel comfortable leaving this year if I didn’t.

I feel very fortunate and honored to have been the CEO, but the best jobs are in the field. I spent 21 years in six countries — Swaziland, Botswana, Grenada, Ethiopia, Namibia, and Malawi — and I wouldn’t trade that time for anything. The health workers you get to work with are very inspirational. They’re brilliant. They know what to do, they just need support in doing it. And it’s very rewarding to see that materialize.

Carol Fredriksen

SS HOPE, Land, HQ

In August 1969, I was working as Chief Medical Technologist at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover, New Hampshire. Another technologist at Hitchcock had served with Project HOPE in Ceylon and told me about a vacancy for a chief technologist on the SS HOPE for the Tunisian voyage. I applied for the position, was interviewed at the airport in Washington, D.C., and was accepted for the voyage. That was the start of 31 years with Project HOPE.

I took the bus from Portland, Maine to Wilmington, Delaware to get to the docks. Toward the end of the voyage, Dr. Walsh asked me to stay with Project HOPE as a full-time employee. I accepted, and soon after reported to the Washington office to prepare for the Jamaican voyage. I represented the non-nursing health staff. We traveled Jamaica crammed into a van without air conditioning. The Jamaicans were most gracious upon arrival at each hospital and clinic.

My next voyage was to Brazil, and this time, I watched the ship set sail and then flew to Natal to prepare for its arrival. The Maceio, Brazil voyage followed. The sad aspect to this voyage was the announcement that the ship would be retiring. Dr. Walsh asked me to stay with Project HOPE though, and I returned to headquarters to represent the allied health profession. A few years later, this led to a position as Director of Personnel, then Director of Administration for the Millwood campus, and finally Director of Program Administration for the International Division focusing on grants management and financial aspects of the programs.

The reason I stayed with Project HOPE was job satisfaction. The students and counterparts in each of the countries in which I served were seriously interested in learning. The staff with whom I had the honor of serving were tops.

I lived through three transitions with Project HOPE. The first was the transition from the ship to land-based programs. The second was the transition from headquarters in Washington, D.C. to Carter Hall in Millwood, Virginia. The final transition was from a leadership by the Walsh family to that of others. In each case, Project HOPE continued to be alive through its commitment to helping others help themselves.

I learned there was more than one way to do something and perhaps our hosts had a better way than we did. Our approach was to learn our hosts’ systems from our counterparts and talk together about options to make things better. If the counterparts were not ready to change, there was no use in trying to push a change. Change had to come from them. In many cases, demonstrations on the ship resulted in changes in methodology within the host’s institutions.

Did you know?

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan conferred the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Dr. William B. Walsh for his lifetime of service. “Dr. William B. Walsh has spent a lifetime giving hope to others. Dr. Walsh is reaching people wherever there is need and, as always, is giving of himself so that others might find hope. He is a credit to his profession and his country,” the President said.