Faces of HOPE: Community Health Workers

In Houston and McAllen, Texas, community health workers are the critical link between their communities and local clinics, going the extra miles to earn trust and reach the state’s most underserved populations.

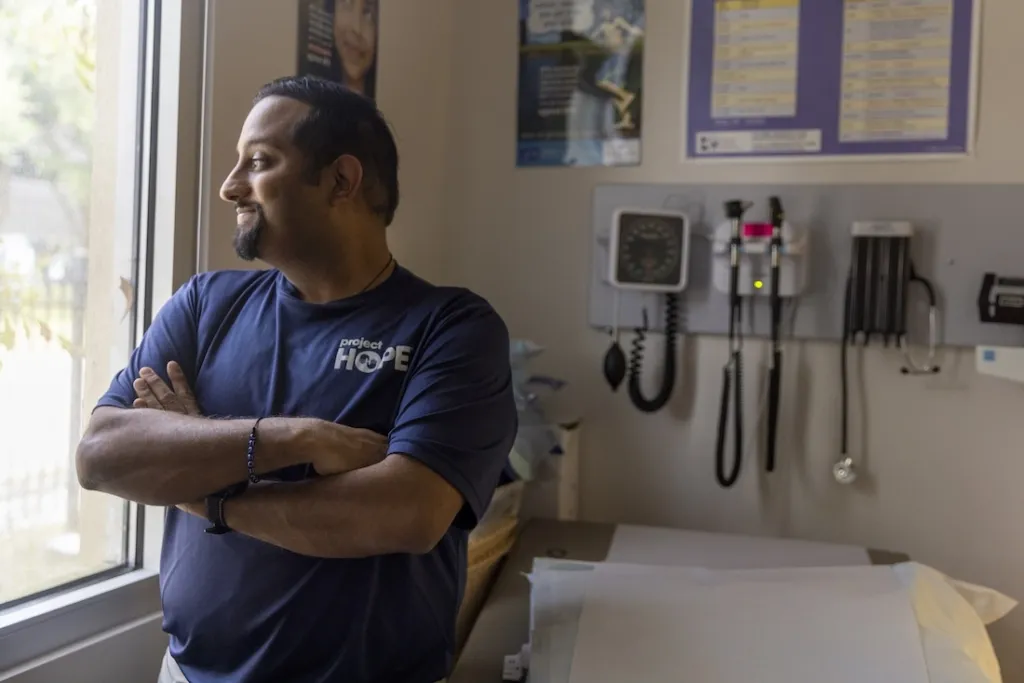

Esteban Ramirez felt the impact of COVID-19 firsthand when everyone in his family caught the virus — himself included. His diabetic father was hit especially hard.

Esteban lives in McAllen, Texas, just a few minutes from the U.S.-Mexico border. As a community health worker, he works inside his community to answer questions and connect people to the vaccine.

“I feel like I’m doing something good for the community, something that’s going to benefit them,” he says.

Esteban works for Hope Family Health Center, which serves the Rio Grande Valley’s low-income and uninsured populations. He’s about to finish his bachelor’s degree, and his dream is to become a physician’s assistant — this job is his first step into the field of health care. He spends a lot of his time countering misinformation and reassuring people from “really different walks of life” of the safety of the vaccine.

Every mind changed, he says, is a step in the right direction.

“I even talk to patients’ relatives. I had a lady who said, ‘Can you talk to my son? He’s the one who’s telling me that it’s not really safe.’ She was here in the lobby of the clinic and she called her son and I talked to him,” he says.

On a warm December morning, a woman named Julia waits outside the clinic after receiving her vaccine. Her husband wasn’t able to get off work and join her, she says, but Esteban assured her he would follow up.

“My husband couldn’t come because he leaves for work at six in the morning,” Julia says. “He has been thinking twice about getting the vaccine because of the problems he had with the last one. He had symptoms for about three or four days… So he wanted to finish work, because if he gets it and has a reaction he won’t be able to work… Esteban told me that he would call my husband so he could make an appointment for him.”

The strides Esteban and other community health workers take every day have become essential in Texas, which ranks 33rd nationwide in the race to get vaccinated. In Houston and McAllen, in particular, there remain critical gaps in access for marginalized communities. But clearly, access isn’t the only problem — many people remain hesitant about the vaccine.

“I feel like I’m doing something good for the community, something that’s going to benefit them.”

– Esteban Ramirez, Community Health Worker, Hope Family Health Center

Through a program funded by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, Project HOPE is improving access through a coalition of free and charitable clinics in Houston and the Rio Grande Valley. This work hinges on community health workers like Esteban, who work tirelessly to build trust with their communities and convince residents to get the care they need to stay healthy and safe. Over the past year, they have helped us vaccinate more than 2,000 residents in McAllen and the Greater Houston area. They’ve also reached over 23,500 people with information on COVID-19.

Community health workers have always been an essential part of Project HOPE’s work around the world, in places like Malawi, Ethiopia, and Haiti. Now, in the U.S., these workers are helping expand our footprint beyond clinic walls to reach everyone who needs care.

In places where health care systems are hard to access or totally out of reach, community health workers are a bridge for families who struggle to access quality health services.

Lesly Galvan, a community health worker at El Milagro Clinic in McAllen, says lack of insurance is one of the biggest barriers to care she sees. Like the Hope Family Health Center, El Milagro is considered a safety-net clinic, which means it serves patients who are low-income or without insurance.

“Before this program, we could only offer COVID-19 vaccines on Fridays. Now we do it every single day,” she says. “A lot of people don’t have the money to go and see a doctor. The services we do here are completely free… we don’t charge a single penny. If we weren’t offering the services, they wouldn’t be getting the help they need.”

For some patients, getting the vaccine is simply a matter of overcoming hurdles to access — they may want to get vaccinated but can’t afford to miss any work or school, or they don’t have any means of transportation to their local clinic. To reach these populations, El Milagro set up a mobile clinic in a neighborhood outside McAllen.

Lesly looks forward to her time at the mobile clinic each month — she says people who show up are generally more curious and comfortable about the vaccine.

‘You Have To Have Some Kind of Connection’

In Houston, Project HOPE is supporting two additional safety-net clinics, Ibn Sina Clinic and San Jose Clinic, which was able to hire three community health workers, including 20-year-old Jacqueline Ochoa.

Every week, Jacqueline goes door-to-door in local communities to educate families about the vaccine. She’ll often make repeat visits, returning to the same home as many as six times before its inhabitants feel ready to get vaccinated.

A self-described introvert, at first reluctant and out of her comfort zone, Jacqueline has learned to love these visits and the opportunity to develop relationships with so many community members — many of them Afghani refugees and other recent arrivals.

She’s discovered that most vaccine hesitancy is a result of lack of education, which has made her feel more empathetic.

“Public health has shown me that one of our biggest issues is misinformation on the internet and social media,” she says. “One of the most important things that I’ve noticed is that in order to get through to people, you have to have some kind of connection and trust.”

At weekly vaccine drives, people often approach her to thank her for giving them the vaccine. “I feel like saying, ‘Thank you. Thank you for trusting me,’” she says.

Across town, at Ibn Sina clinic, community health worker and doctoral student Aftab Ali works hard to earn people’s trust and educate community members about the vaccine — sometimes even his own co-workers. He spent several months working to convince a fellow co-worker to get her first dose.

“It took a lot of facts, a lot of history, a lot of lessons, and a lot of statistics,” he says. “I was so proud of her.”

Aftab’s community is very important to him, and he’s passionate about his work. His goal is to make sure people know they can trust their health workers, and that they have the knowledge they need to make informed decisions and “take the step toward a healthier future.”

He often shares his own story to relate to patients. He caught COVID-19 in April 2020, and had only mild symptoms. But months after testing positive for the virus, he experienced heart issues for the first time in his life — his doctor found blood clots and traced them back to the same time period he was exposed to the virus.

The experience has motivated him to meet people where they are in their own journeys, and help them trust that these clinics are only there to care for them.

“This is not the first pandemic that we’ve dealt with and it won’t be the last,” he says. “I want to make sure most of our population is serious about it. I want people to understand we’re here to help.”