On the Ground: Humanitarian Work in Gaza is More Dangerous Than Ever

Read a dispatch from Project HOPE’s team lead in Gaza about the dangers his team faces and the intense difficulties facing Gazans every day.

Most of the roads I see each day are crowded with people: some in cars, some in lorries, but mostly traveling in carts pulled by oxen or horses. They’re moving in families, carrying everything they own. Gaza has become a mass movement of people after last month’s invasion of Rafah. And the situation is desperate.

Many of the 1 million people forced to flee have evacuated toward the middle areas of Gaza, to cities like Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah. Because there are very few access corridors for humanitarian aid into Gaza, most internally displaced people (IDPs) do not have shelter, clean water, or food. Most of the humanitarian organizations who supply IDPs with tents have run out of tents.

The food security situation is even more dire. Very little food is entering into the market, and the little which is there is extremely overpriced so many people can’t afford what little food is in the market. Flour is scarce and expensive. Cooking gas is not easily available. Most bakeries have closed. Most women and children do not have enough to eat, and most households are down to eating one or two meals per day as a coping strategy. We rarely find meat. Our team relies mostly on eating canned beef, canned beans, and rice. Just recently, we tried to find bread for breakfast but it wasn’t there — because there was no fuel.

Running a humanitarian operation takes fuel, and most humanitarian organizations right now do not have enough to run the few remaining field hospitals or provide water points. There is no fuel in the market. The recent bombardment in Rafah that killed 45 people was very close to the logistics space where we get fuel each day for our operations, jeopardizing what little access we had. As of a few days ago, a liter of fuel was going for $22—or $83 a gallon.

The sounds of war have become a daily routine. Drones fly above you 24-7, always overhead. You hear them throughout the day, but especially at night and just before sunrise. The sounds of planes and bombs become very intense at night.

I was in Yemen for three years before I came here. I’ve also worked in Iraq, Syria, South Sudan, and the Philippines. This context has been the most challenging. It’s very dangerous. Recently, I traveled the crowded roads to Deir al-Balah. A distance of just 15 kilometers took two hours because of the crowds. If a target is identified, then it’s very, very dangerous to be in a crowd. Our team left our previous guest house because it was no longer safe; active fighting was less than five minutes from our door. A recent explosion hit only a few hundred meters away.

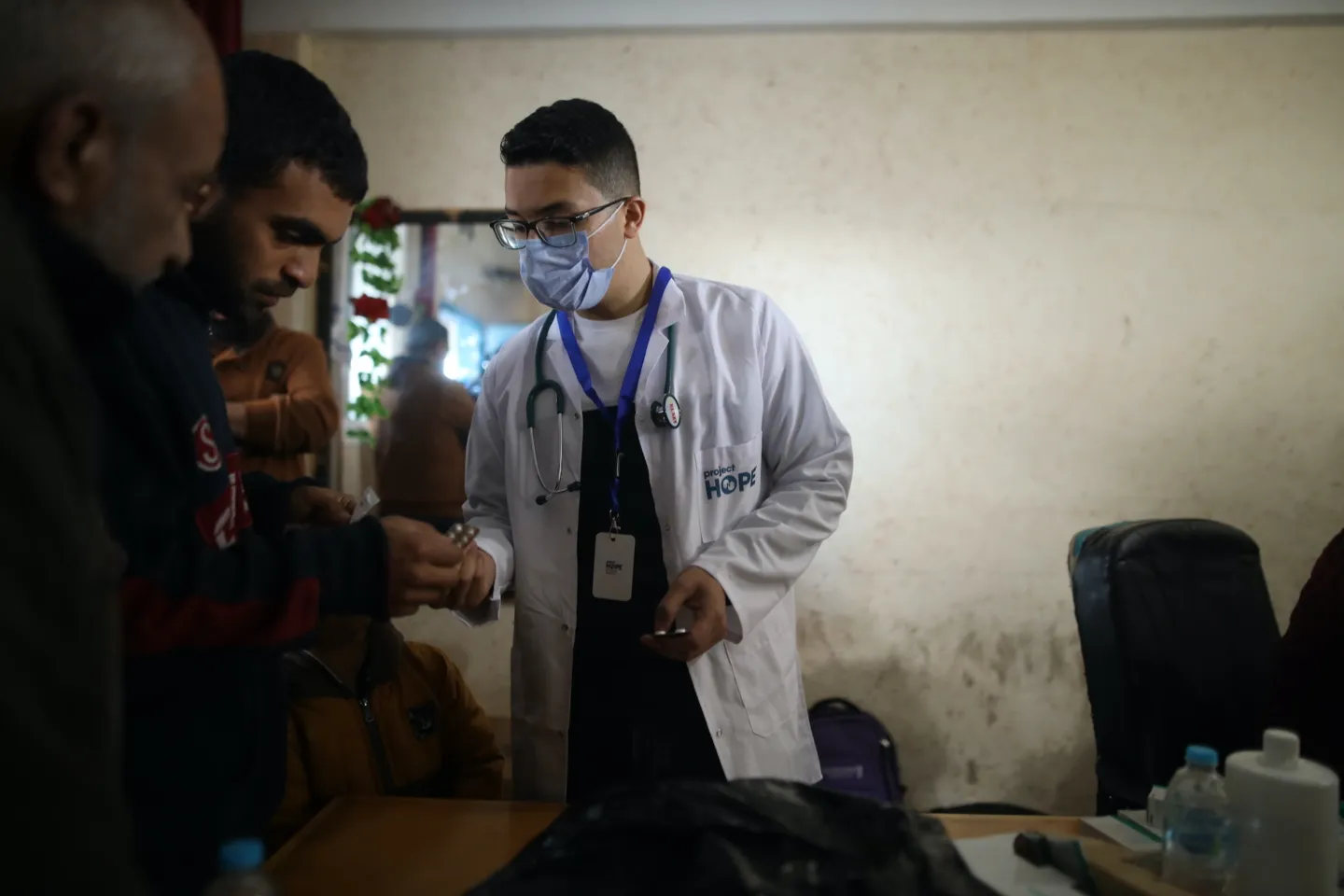

Most of the hospitals are overwhelmed because of the casualties coming from the constant bombardments. Because of the limited capacity of the facilities in Rafah, the most reliable facility right now offering major surgeries is Al Aqsa Hospital where some of our team is working. Recently I made some visits there to meet with our emergency medical team. I wanted to understand how the situation has been and what sort of support they have been giving to the patients.

The staff told me how they managed to attend to people who were injured in the recent bombing in Rafah. Most of the patients had severe injuries that needed emergency surgery. The surgeries were complicated. Shrapnel needed to be removed extremely gently as it was affecting liver and kidney function. The doctors had attended many people with severe burns covering 50 to 90 percent of their bodies. One doctor told me that the last patient he saw, he had done his best, but unfortunately she passed on because she had severe burns on more than 90 percent of her body.

We have seen a rise in cases of acute diarrhea and are starting to see outbreaks of hepatitis A and B. We have also seen an increase in the number of people being discharged from health facilities who have nowhere to go, including children who have lost their parents and do not have anyone left.

Everyday services in Gaza are very difficult, if not impossible to find. Everything is down. There’s no banking system. There’s no fuel. There’s nothing in the market. Humanitarian aid is not coming easily across the borders. If you want to move, you have to notify officials and wait for a green light. A lot of humanitarian workers, including one of our own, have died.

Yet an environment like this can also teach you many things. I’m used to adapting to the challenges. Having worked in other crisis locations, I’m able to adapt to the circumstances. You need to think outside the box, otherwise you cannot function. But the war here is very dangerous, and fighting is always close. Recently, there were active engagements while our teams were rotating in Kerem Shalom, just 20 meters from where they were passing.

My message would simply be that we are calling for peace and a ceasefire agreement to be reached, because people here are really, really suffering. People are desperate and do not have anything. You can’t imagine what it’s like for more than 1 million people to be crammed in such a small area. People fight just to get water when a truck appears. It’s a catastrophe of a situation. Women and children, especially, are suffering. Every one of their lives is in danger if something is not done.

Moses Kondowe is Project HOPE’s team lead in Gaza.