‘You Can’t Explain How Bad It Is if You Haven’t Actually Been There’

When COVID-19 devastated New York City, it presented an unprecedented new challenge for the city’s hospitals: protecting the mental health of those on the front lines.

COVID-19 has exposed devastating vulnerabilities in the world’s health systems, including the lack of mental health support for frontline workers. And few places have been tested like New York City.

As COVID-19 cases began inundating the city’s hospitals, it threatened not just the physical health of New York’s health care workers, but their emotional and psychological health as well. NYC Health + Hospitals, the nation’s largest municipal health care system, responded by offering several new resources to support their staff’s mental health through the surge, including respite rooms, free childcare, a behavioral health hotline, and mourning rooms.

So what kind of difference did this support make for New York City’s health care workers? And what can we learn from a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic? Learn more in this Q&A with Dr. Eric Wei, Senior Vice President and Chief Quality Officer for NYC Health + Hospitals.

This article you co-authored for Health Affairs mentions a tradition of stoicism in medicine and a stigma toward mental health that keeps many health workers from asking for help. Why does that stigma exist? And do you think COVID-19 has been a shock to the system, highlighting the importance of this care?

There’s no doubt that COVID-19 has changed everything, both in people’s personal lives but certainly within health care and the workplace. There were cracks in the foundation, and COVID turned them into gaping valleys. The emotional and psychological support of health care workers was one of those.

We’ve certainly had heartbreaking loss through depression and suicide, but I believe we’ve been able to stave off our worst nightmare of having a mental health crisis on top of a public health crisis. The culture and tradition in medicine is that it takes a very tough, very special breed of clinician, nurse, or health care worker to be able to survive the stress of a career in a hospital or clinic setting. Medical training and nurse training is almost like a boot camp in the military — it’s meant to desensitize you or toughen you up so you can handle it.

On the nursing side, there’s a saying that nurses “eat their young.” The idea is that they treat their new nurses poorly in order to toughen them up. And on the physician side, it’s very much an attitude of, “What I went through is even worse than you went through today, so you should just suck it up and stop complaining.”

It’s a complete contrast to how we treat our patients all day long. All of us went into health care to make people better and support them as an entire person. It’s ironic that we treat each other like that.

When it first became clear that COVID-19 was going to cause significant psychological trauma for the hospital staff, what did you do to scale up your support systems to meet the need? What was the sense of urgency in those early days to get these systems in place fast?

We were very lucky to have the Helping Healers Heal employee wellness program, which was the first thing [NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO] Dr. Mitchell Katz agreed we’d bring with us from Los Angeles. We were fortunate to have two years to build up that support system before the pandemic hit. But the other thing that made a big difference is that we have very strong behavioral health services across the hospital system. Our hospital system provides over 60% of all behavioral care in New York City.

So I think we were attuned to it even without a pandemic — this idea that there’s emotional and psychological trauma that comes with taking care of people in a hospital and clinic setting. We were already doing this work, and that helped us identify the threat. We realized, “Holy cow, there’s a once-in-a-century global pandemic coming our way. This is going to mean extra emotional and psychological support for our staff.” Everything that we put in place — training up additional supporters, setting up a behavioral health hotline, establishing wellness and respite rooms, doing wellness rounds, leveraging 1-on-1 debriefs across the system, sending comforts to our providers — all of this was kind of a natural escalation of the work we were already doing.

One of the ways the hospital system supported staff was by offering free daycare and hotel rooms for staff who needed to isolate away from their families. The need for child care has been a major conversation during the pandemic. What was the connection you saw between child care and mental health, and why did you want to prioritize that support?

We were just talking about this in our central leadership cabinet meeting today — about the heartbreak of single parents who are health care workers trying to navigate fully remote or hybrid school, especially now that they’re talking about pulling back on reopening hotspots in New York City. But even for those who aren’t single parents, it’s incredibly challenging to not know what’s going to happen with schools and who’s going to care for your child. Layer that on top of the fear of, “What if I get COVID and I’m one of the unlucky few who gets really sick or dies from the virus? Who’s going to take care of my children?” It’s heartbreaking stuff that people were having to make choices around.

I can use myself as an example. I remember the first weekend in March, doing my normal Saturday routine with my two girls: ballet class, then pizza, then swim class. Then, that Monday, I went to work an emergency department shift and my wife and I had a long discussion about making the heartbreaking choice for me to isolate from the family knowing the virus was in New York City and we had a three-week-old at home. My wife was basically on her own with a newborn, 3-year-old, and a 5-year-old, with me isolating away from them. It was incredibly challenging.

We felt lucky that we had the means for me to isolate away, but many people don’t have as many options as we had to make it work. We felt that providing child care support and hotels for staff who need to isolate away — who maybe live in an apartment with only one bathroom — that offered peace of mind for those who were serving heroically to suit up in these emergency departments.

You mention in the Health Affairs piece that even when staff weren’t utilizing formal support resources, they were talking to each other through group chats and texts. That peer-to-peer emotional support seems like it was really important for staff. What do you think you can learn from that?

Our Helping Healers Heal program is built upon peer-to-peer support. When I was working shifts, it was incredibly important to me and my team members that we had this shared lived experience of being on those front lines, treating these patients and doing everything we can, sweating through all this PPE and trying to save as many lives as we could.

I had some conversations early on in the pandemic that really stuck with me. I had emergency department providers tell me they actually felt safer and more supported while they were at work. You’re in PPE and the virus is all around — obviously it’s not safer for you physically, but from a psychological standpoint, these people who go into battle with me shoulder-to-shoulder know how I’m feeling and they’re feeling the same way. It’s almost like an unspoken “I know what you’re going through” feeling that you might not get working in finance or the stock market. You can’t explain how bad it is if you haven’t actually been there. That was a critical part of healing. The support came through just being with those who had been there, too.

Part of the support you provided included mourning rooms for people to grieve lost colleagues. What role do mourning and grief play in emotional health, and why is it important to face them head-on?

Not only was there the fear of the unknown with the virus and how it could threaten the health of health care workers and their loved ones, but our staff were seeing colleagues and family and friends get sick. I think it was very hard to live in New York City and not know somebody who got COVID and maybe even died of COVID.

As human beings we are wired to heal, to grieve, and to mourn with those we love — through being with each other at funerals and wakes and memorials, hugging each other, breaking bread and having meals together in memory of lost loved ones — and COVID took all of that away. We had to socially distance before doing memorials via Zoom. You weren’t allowed to go to funerals, or the number of people who could go was very limited.

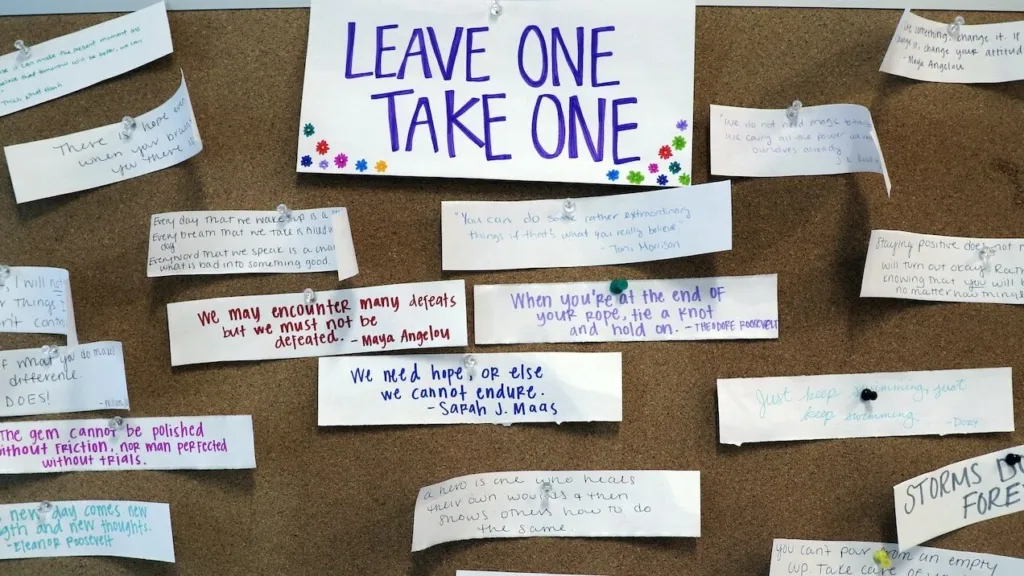

I began seeing staff create makeshift memorials. King’s County Hospital lost a beloved overnight charge nurse to COVID and they set up a desk in the main hallway with a chair that said “Reserved” with her name on it, with a bulletin board where people left handwritten notes and posted pictures. There were flowers on it and somebody left her favorite candies on it. People were trying to be as creative as possible while being safe, to set up these sorts of memorials.

The mourning and grieving rooms were a way to create a safe space for staff to post messages to go and remember loved ones and colleagues, to find resources in a socially distanced way, to speak to someone or find comfort just being in the company of others in a safe way. It was something very meaningful to the staff. We can’t heal in the way we’d normally do it, but there’s a safe space we can go to refresh and remember. It was in response to another way the virus robbed us.

Project HOPE is piloting the HERO-NY training in Indonesia and the Dominican Republic. Why is this training particularly valuable for frontline health workers in developing countries where mental health support isn’t available?

Even though we had a program like Helping Healers Heal, the Department of Defense and U.S. military had something very unique and valuable to share, and that is what combat stress can do to the human mind. We’re very grateful to General [Terrance] O’Shaughnessy and the Department of Defense and our entire military for being generous and proactive and wanting to share those hard lessons about how they support soldiers throughout combat stress.

Many people have made analogies to war with what COVID has done in health care settings across the world. While I’m non-military and have never been in a combat scenario, the Department of Defense providers and staff embedded in our hospitals were telling our leadership, “This feels like it.” This was the closest they had ever seen in a civilian setting.

That lived experience — whether in Indonesia, the Dominican Republic, or anywhere — makes it feel very combat and war-like. You’re fighting a tremendous enemy in the virus that is causing a tremendous amount of severe illness and death.

To be able to take that combat stress management and resilience training and be able to share that with health care worker civilians so that they’re better equipped to handle that stress, I think that crosses languages and cultures and countries. So I’m glad Project HOPE is sharing this across the globe, because even though we care about our own health care workers here in New York, we also care about health care workers anywhere. I think the HERO-NY acronym really reflects those who ran toward the fire and continue to fight this virus.

Eric Wei, MD, MBA, is Senior Vice President and Chief Quality Officer for NYC Health + Hospitals.