The Ripple Effects of a Hurricane

Hurricanes have ripple effects that can resonate through health systems for years after a storm strikes. And marginalized communities feel them the most.

Recent Atlantic hurricane seasons have been some of the most active in history, with 85 named storms triggering massive displacement and inflicting billions of dollars in damages just since 2020. And because of climate change, it’s projected that storms will be even stronger and more frequent in the years to come.

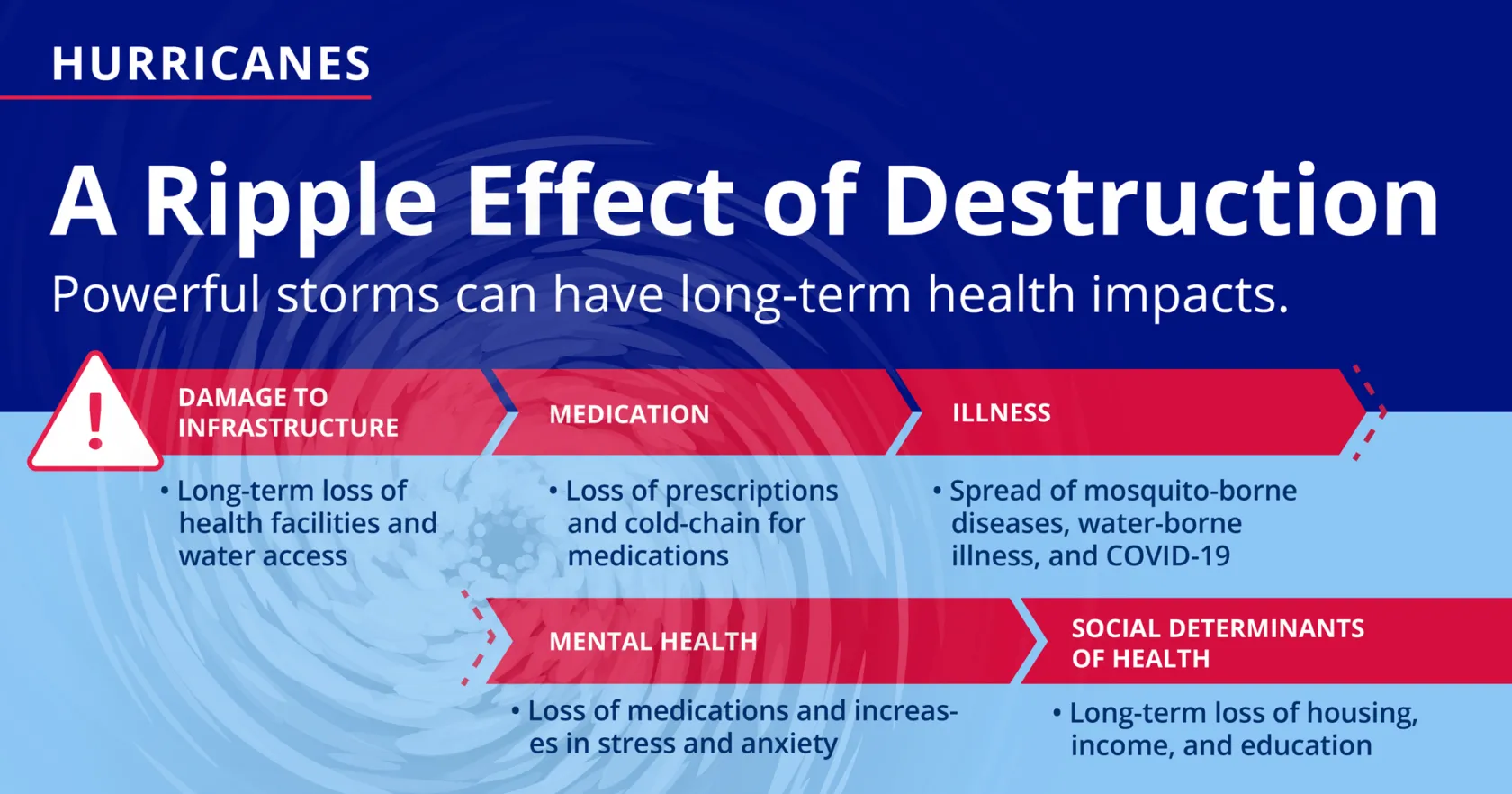

Many of the direct threats of these storms stand front and center: injuries, death, and destruction are the immediate impacts many of us think of. But there are also many longer-term impacts that can impact public health long after headlines fade.

1. Long-Term Damage to Infrastructure

Damage to infrastructure can have a domino effect on public health and health systems that lasts for years. Damage to hospitals can impact regular care, surgeries, emergency care, and can lead to losses in critical medical equipment. Damage to water systems heightens the risk of mosquito- and water-borne illnesses like malaria and cholera, while disruption to power grids affects refrigeration and creates a risk of environmental contaminants.

Rebuilding never happens overnight. It has been three years since Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana, and many communities are still in recovery, rebuilding from widespread flood and wind damage. Two full years after Hurricane Dorian struck the Bahamas, there were still mounds of debris across the island and families living in shelters next to where their homes used to be.

2. Loss of Medicines and Prescriptions

Though trauma care and injuries are often the focus of hurricane recovery, the loss of medicines and prescriptions as a result of storm damage can have a serious, long-term impact on health. This issue is especially serious for those who have chronic health issues like diabetes or heart disease — conditions that persist long after a storm passes. One study found up to 40% of those affected by Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita to be living with a chronic illness.

The loss of cold chains also threatens the supply of lifesaving medication like insulin, as it did in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, where more than 15% of people were living with diabetes when the storm made landfall. That would be like the entire population of Atlanta losing access to insulin in an instant.

3. Spread of Life-Threatening Illness

Physical injuries make up only a fraction of the disaster death toll. Research has linked hurricanes and tropical storms to an increase of up to 33.4% in death rates in the months after a disaster — a number that includes deaths from infectious and parasitic diseases that can occur months after a storm makes landfall.

Researchers have found that while storm deaths from injuries generally occur within days of landfall, deaths due to disease don’t peak until one to two months later. In the aftermath of a storm, when water systems are compromised and homes are destroyed beyond repair, the risk of infectious outbreaks is dangerously high — especially for families forced to live in shelters. After Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, a gastroenteritis outbreak spread among the 27,000 evacuees housed in a single “megashelter” in Houston, impacting more than 1,000 people. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, families displaced by storms have had to risk infection to put a temporary roof over their heads.

The death toll continues to climb for years — not just months — after a storm hits. New research from Stanford University links hurricanes to higher death rates for 15 years after storms take place, indirectly causing up to 11,000 excess deaths. It’s estimated that tropical storms in the U.S. have contributed to as many as 5.2 million excess deaths since 1930 — more than fatalities from car accidents, infectious diseases, and wars.

4. Damage to Mental Health

Hurricanes leave invisible scars, too. The emotional and psychological damages from living through disaster run deep. Survivors are at increased risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety — the most common mental health impacts of hurricanes. And sometimes these symptoms last a lifetime — especially when mental health services are limited and pushed to the wayside during times of crisis and emergency.

Many hurricane survivors don’t just lose access to medicines or hospitals; they also lose access to therapy. The timing couldn’t be worse: After Hurricane Katrina, the prevalence of probable serious mental illness doubled among low-income parents, with nearly half of all respondents in one study exhibiting signs of PTSD. Another study found that mental health issues among children persisted up to four years after the disaster.

5. Impacts on the Social Determinants of Health

A person’s health is not just determined by genetics or family history. It also depends on social and economic factors like where they live, how they make a living, their level of education, how well they can access healthy food, their social and community context, and discrimination. These are the social determinants of health, and they all affect a family’s ability to access care. Low-income communities and communities of color are usually at the greatest disadvantage, and when a major hurricane hits the impacts can be devastating.

“Like many other catastrophic events, marginalized communities already struggling to survive are most disproportionately impacted,” says Kimberlyn Clarkson, chief advancement officer at San José Clinic in Houston, Texas.

“Many Houstonians have yet to be able to fully restore their homes after Hurricane Harvey … Neighbors that were left without work have struggled to find consistent work in the five years since the hurricane.”

Kimberlyn Clarkson, San José Clinic, Houston

San José Clinic is the leading charity care provider of health services for the underserved in the Greater Houston area. In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Project HOPE helped Clarkson and her team set up mobile clinics to reach more residents in need of care.

One of those mobile clinics was converted to an outpost serving a rural community an hour outside the city.

“Many Houstonians have yet to be able to fully restore their homes after Hurricane Harvey,” Clarkson says. “Additionally, neighbors that were left without work have struggled to find consistent work in the five years since the hurricane.”

At the clinic, her team has seen unusually high incidences of chronic respiratory illness among marginalized communities, which they link to mold caused by flooding from the storm.

Having lived on the Gulf Coast for most of her life, Clarkson has seen countless occurrences of devastation caused by storms.

“I’ve seen parents that rely on the free breakfast and lunch served at school unable to ensure adequate food for their children when schools have to be closed. I’ve worked closely with families barely able to pay rent and unable to secure safe housing when their homes have been flooded and shelters are full. And even sadder, I’ve witnessed many of our neighbors that lack access to resources and transportation trying to figure out how to evacuate their families ahead of storms. The thought of facing imminent death and destruction with no ability to save your family is a crippling reality for so many.”

As future hurricane seasons loom, she worries about her patients’ ability to find care if they are forced to leave home — an increasing concern as climate change intensifies and major storms become more likely. “If they are able or willing to evacuate outside of the Houston or Gulf Coast area, where will they receive treatment at low or no cost? As a neighbor and fellow member of a marginalized community, I worry about children and families already in need of equitable solutions gripped with the fear that their situation can be worsened overnight if another devastating storm hits our area.”