‘Breathtaking’ Destruction: A Q&A On Hurricane Dorian’s Aftermath

As the scale of Hurricane Dorian’s destruction comes into focus, Bahamians on the islands of Abaco and Grand Bahama face a monumental recovery. Learn more in this Q&A with Tom Cotter, Project HOPE’s director of emergency response.

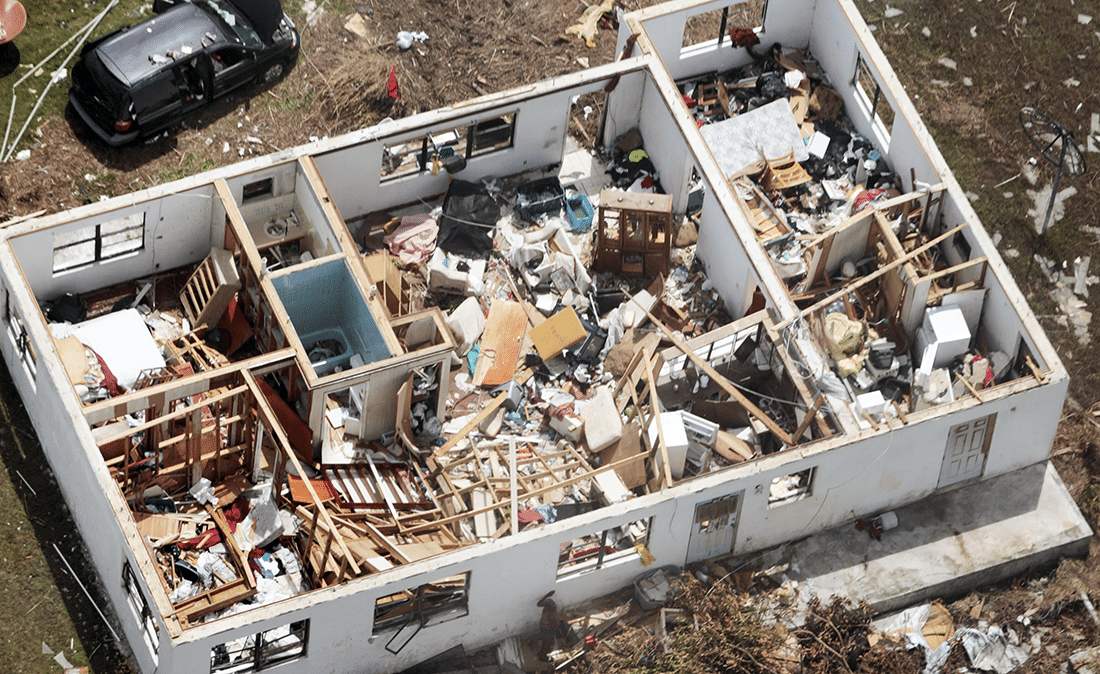

When Hurricane Dorian slammed into the Bahamas on September 1, it left Abaco and Grand Bahama Island in ruins. Winds of 200 miles per hour ripped apart buildings, while catastrophic floods wiped away entire neighborhoods. It will take some time to understand the full scope of need, but government officials have warned that the storm’s death toll could be “staggering.”

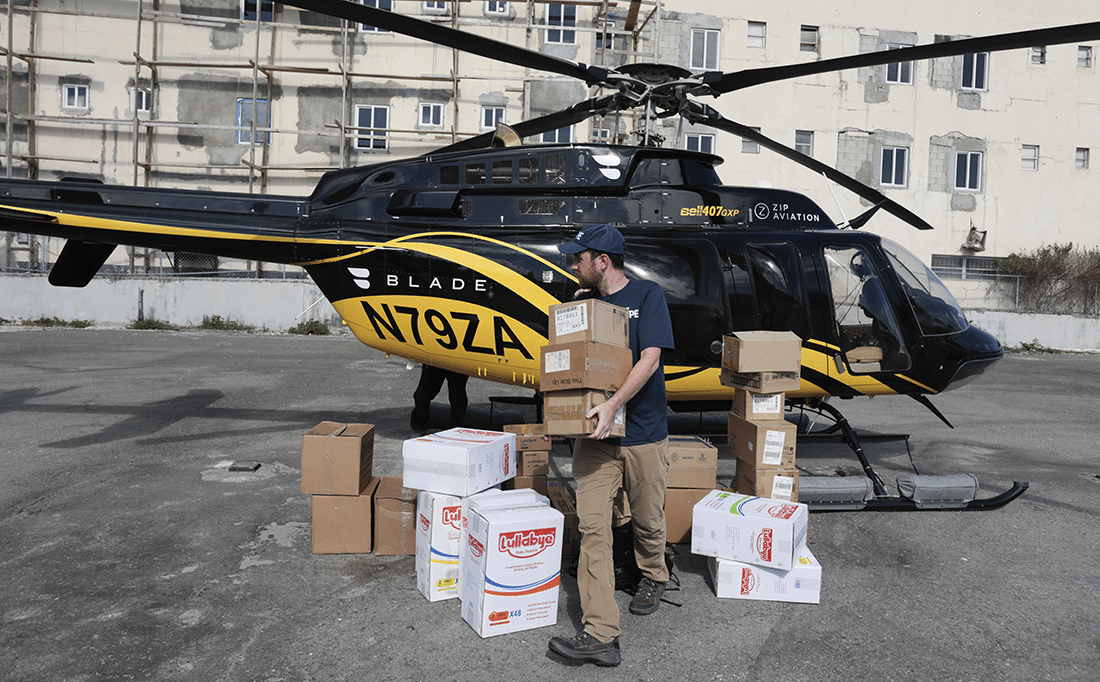

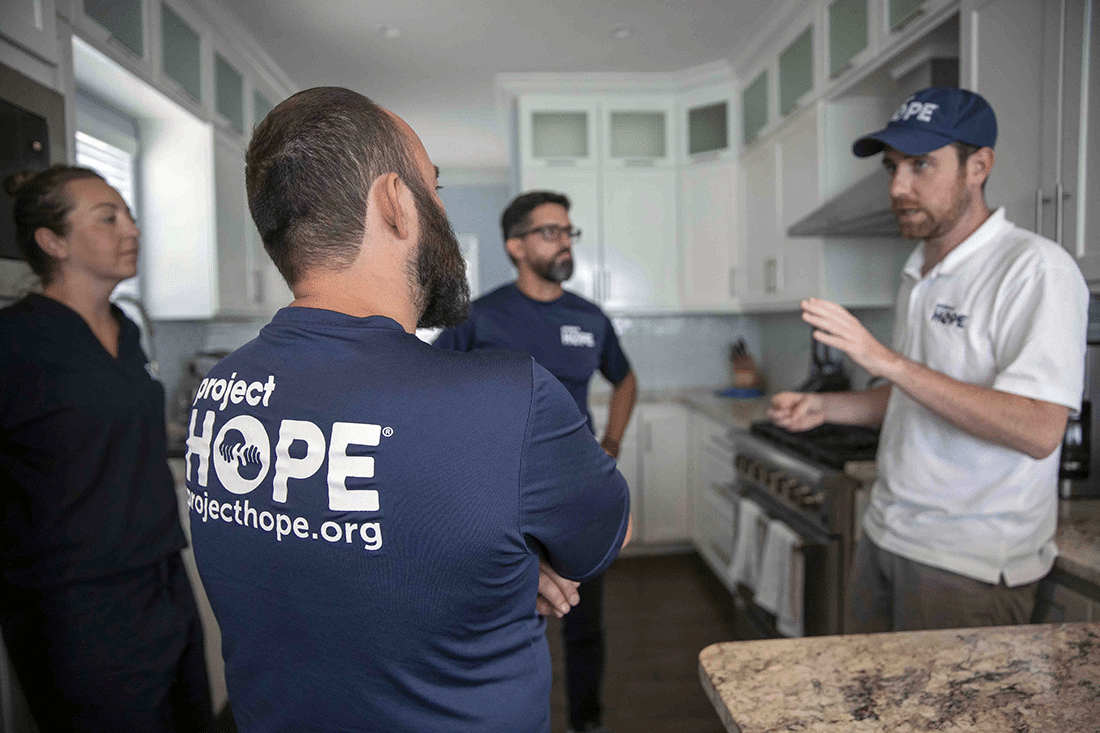

Project HOPE was on the ground in the Bahamas just days after the storm, assessing the greatest needs and distributing essential medical supplies to the hospital on Abaco. Today our emergency response team is providing health care for evacuees in multiple shelters around Nassau while supporting Abaco as they begin the long road to recovery.

Read “Hurricane Dorian: What You Need To Know”

Tom Cotter is Project HOPE’s director of emergency response and preparedness and was on the ground in Abaco shortly after the storm passed. In his career, Cotter has responded to major disasters including Hurricane Matthew, Cyclone Idai, cyclones in the Philippines, polio outbreak in Nigeria and major earthquakes in Haiti and Papua New Guinea.

Read on to hear what conditions are like in the storm’s hardest-hit areas, how Project HOPE is meeting immediate needs and what you can do to help.

Q: What’s the general attitude among the people there? Are they stunned at what happened? Are they determined to recover?

A: I think stunned is a good word. A lot of people are anxious about the future. They don’t know what’s going to happen next. They don’t know when they’ll be able to — or if they even want to — try to resettle where their houses once were. I think they’re taking it literally hour by hour, day by day, which can be expected right now.

Q: How were you able to get to Abaco so soon after the storm passed?

A: I’ve been doing emergency response for nearly a decade, and this is one of the worst disasters I’ve ever responded to. It was really, really difficult to get to the affected islands. Through a local partner we were able to secure one seat on a charter plane. As the plane approached, the trees were completely bare; they had been snapped in half or were missing all of their needles. The water around the island was completely littered with debris — cars, houses, sunken boats, all kinds of debris. The extent of the damage was breathtaking.

As the plane was landing, my first glimpses of the town were that I was looking into people’s bedrooms and bathrooms. There were no roofs on the houses. It was really emotional to see. Folks were dazed, just sitting on their porches sifting through rubble.

Q: Why was it important to connect to local partners immediately, and how did you go about that?

A: We have two immediate objectives after a response is launched and we get on ground. One is to start doing immediate lifesaving activities, wherever it is. And the second is to get tapped into coordination.

When a response hits, some of the first coordination we do is to reach out to some of our partner donors who are committed to supporting us as we do high-quality, fast response. They’re critical to making sure we can have the most impact as soon as we hit the ground. When we get there, we want to coordinate with the authorities — in the Bahamas, that’s the National Emergency Management Agency and, for us, the Ministry of Health. They know their neighborhoods best.

When we landed, we got in touch immediately with an organization called Restoration Abaco. This is a group of women who are from Abaco, they evacuated to Nassau before the storm, and when they saw what happened to Abaco they essentially quit their normal jobs to start this nonprofit. The day the storm hit they filed their paperwork. They didn’t wait. They said, somebody’s got to do something, we’re here, let’s do it. And because we also have that attitude, we formed a really good partnership that allowed us to hit the ground running. I went from the airport to their office and back to the airport to fly to Abaco, and that was less than 24 hours after the airport opened back up. That’s remarkable. Communities helping communities is fantastic.

Q: What’s difficult about responding to an emergency on an island?

A: The short answer is everything is more difficult. In Caribbean islands like the Bahamas, their elevation is quite low, they’re surrounded by water and they’re not very big. So when a storm is approaching, there’s nowhere to go. There’s nowhere to hide. When a storm hits an island, it’s going to hit every part of the island without exception. That’s a major challenge and really exacerbates the impact of the disaster.

Logistically, it’s a nightmare. Everything has to be flown in or taken by boat. Because of the debris in the water, you couldn’t take a normal boat — it had to be steel-hulled, not fiberglass. Land transportation is really, really difficult. Communications is still largely down on Abaco Island. When we get there, we can’t call headquarters, we can’t call our team, we can’t reach out to partners, we can’t call the helicopter to let them know we’re coming. Everything has to be done in person.

Q: Do you feel like people expected it to be this bad or were they caught by surprise?

A: Even I didn’t expect it to be this bad, so I can only imagine what the Bahamians were thinking. It was breathtaking to see the destruction for the first time. Bahamians have had hurricanes before, so I think a lot of people thought it was going to be like any other storm that they rode out, where they did some repairs and got back to their homes. Not a lot of people evacuated right away — some did, but not most. That tells me that people thought it was going to be a lot lighter than it was.

Q: With such overwhelming destruction, what can be done immediately to help?

A: The first thing is that the evacuees need to be helped, and the people who decided to stay need to be helped. It’s not much more complicated than that. We have to make sure that Nassau’s infrastructure can support the additional evacuee population now, and that we get health services restored on the islands. So our approach is simple: We hear the needs, we go and fill the needs as fast as we can, and we keep doing that until there’s no more need. That’s how we cut through the chaos.

But at some point, people are going to want to go back home — maybe not all of them, but certainly some will. We have to have systems in place to support them through reconstruction. It’s difficult to look past the next day or two, but we really need to start taking a multi-week approach to this, which we will. Project HOPE is not only meeting immediate needs, but we’re looking to restore the health care infrastructure in the affected areas.

Q: What are some of your immediate concerns right now?

A: Because of the water and sanitation on the most affected islands, Abaco and Grand Bahama, I’m worried about the usual diseases popping up: diarrheal diseases, respiratory diseases, all the diseases that accompany poor water and sanitation conditions.

The second thing is that people need to make sure their chronic health conditions are met — both evacuees and people who stayed. They need to have good health care and access to their medicine so they can continue to manage their conditions and not get sicker. This includes people with conditions like diabetes and hypertension, but also people with chronic mental health conditions like depression and bipolar disorder.

Q: What’s your thought process when you prepare to respond to an emergency?

A: The thing before every disaster is that there’s no information. Figuring out what is going on is usually job number one when you deploy. One of the things that really struck me when I arrived here is that Nassau is totally fine, but there were no tourists here. The cruise ships had skipped their ports here, and tourists had canceled their plans. So there are two ways to really help the Bahamas right now: one is to donate to us so we can meet people’s immediate needs, and the other is to come visit. They need the economy right now.

Q: How did you get into this work and what keeps you going?

A: I started as a community organizer in Providence, Rhode Island and became an EMT. I was trying to figure out a way to combine those two things, so I got into public health. Because of my EMT background, emergency response was a natural fit.

What keeps me going is different depending on the day. Some days I’m happy, things are going well and we’re providing aid. Other days I’m frustrated, and that motivates me even more. But if there’s only one reason you’re doing this, then when that runs out, you’re done. So you have to find more than one, because it sure isn’t easy.

Q: Have you met any people whose story stuck with you?

A: I interviewed a man who lives near Nassau on New Providence Island. He’s amazing — when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, he went there to do whatever needed to be done. He said, “I lifted boxes, I just helped out moving stuff around, I did whatever needed to get done.” Now this storm hits, and his 15-year-old daughter is in Abaco. When he found out she was alive, he didn’t even have a plan — he went there to get her immediately.

Q: What do you think will be your lasting impression of this trip when you get back?

A: My lasting impression will be how the sense of community in the Bahamas really left everyone affected by the storm. Even if they didn’t get the wind, the rain and the flooding, everyone is affected. That’s not something that’s typical in emergency response.

In an emergency response, you typically get a city, a region or a state that’s affected, but it’s not as though people in New York were particularly affected by Hurricane Katrina. The communities in the U.S. are so separate that we feel a bond of comradeship among our fellow country-people, but we don’t necessarily know them by name. Here, it’s not like that. Everybody knows everybody. That’s what makes this different.