Skin-to-Skin: Alternative Incubation Technique Saves Newborn Lives

Project HOPE introduces Kangaroo Mother Care to new mothers in Sierra Leone, a warming method that simulates the womb and helps premature and low weight babies survive and grow healthy — from fragile to strong.

Sierra Leone has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world — approximately 21 babies die each day before reaching their first month mark.¹ Many of these deaths can be prevented, but only if health care professionals and mothers are provided with the right education and resources. Recognizing this need, Project HOPE is training health workers on Kangaroo Mother Care, an alternative warming method that’s saving the lives and improving the health of vulnerable premature and low birth weight babies.

Musu Yambasu, 40, clutches her tiny new baby girl to her chest, wrapped tightly with colorful fabric, wearing a knit hat and socks on her feet. Musu has a history of giving birth to small babies – this is her seventh – but this is the first to be treated with Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC).

KMC is a method that places the baby skin-to-skin on the mother’s chest, wrapping the tiny infant securely to its mother for warmth. The mother’s warmth and heartbeat simulate the womb, and the baby’s continual contact with the mother – and not much else – helps to regulate the baby’s body temperature, promote bonding and exclusive breastfeeding, and prevent infections easily contracted during the first days and weeks of life.

In countries and regions where hospital resources are limited – and have few incubators, or none at all – the KMC technique can be a lifesaver.

Musu has been in the KMC unit at Bo District Hospital for nine days. She’s bonded more quickly with this baby than she did with any of her others, and she notices that her development and growth is faster, too.

“I’m so happy to have given birth here,” she says. “I’ve learned a whole lot.”

Angella Juana, the head nurse in the KMC unit, has been a trusted mentor to Musu during her time at the hospital. “The care she’s received here is something she’s never experienced before — especially the closeness and the bonding,” shares Angella. “She’s very happy with the treatment, the teachings, the mentorship she’s been receiving, like how to breastfeed, teachings about hygiene, exclusive breastfeeding, danger signs.”

The teaching and mentorship she’s received will stay with her when she goes home – which will be soon. She’ll continue to keep her baby close, wrapped in the kangaroo-like pouch, even while caring for her other six children and taking care of daily household chores.

Bringing HOPE and KMC to Sierra Leone

Project HOPE started working in Sierra Leone in 2014 to help contain the Ebola outbreak, in response to a call for assistance from the government. During this response, we recognized the need for maternal, neonatal and child health programs — and have been working to improve health outcomes for newborns and their mothers ever since.

Promoting the creation of KMC units is an important part of this work. We’ve established the first two units at Ola During Children’s and Bo District Hospitals, where Musu is, with the aim of having these flagship units serve as centers of excellence for learning for other hospitals throughout Sierra Leone.

Over the past two years, these units have served more than 630 newborns.

“The Kangaroo Mother Care initiative is a low-technology intervention for care of small babies through early, prolonged and continuous skin-to-skin contact between the mother and her baby for thermal care,” explains Project HOPE’s Banneh Daramy, a newborn consultant. “Project HOPE trains health workers, who in turn train mothers, how to position and feed their tiny babies, and teach them behaviors for infection prevention and what to do if there are breathing difficulties. The lessons help many premature and low birth weight babies thrive.”

Premature babies need constant warmth from their mothers to survive and grow healthy, from fragile to strong. With the KMC approach, the baby is snugly wrapped to its mother; the warmth created stimulates regular breathing and promotes breastfeeding for babies who have difficulty feeding.

Such tiny, vulnerable infants need to be wrapped KMC-style up to 24 hours a day until they’re able to keep their own body heat and feeding enough to see an increase in their weight. It can take weeks for that time to come, which is why so many premature babies have a hard time surviving.

But the low-technology, low-cost intervention is highly effective, and also offers greater mother-baby bonding opportunities, which Musu can attest to.

Once a curious concept, now a best practice

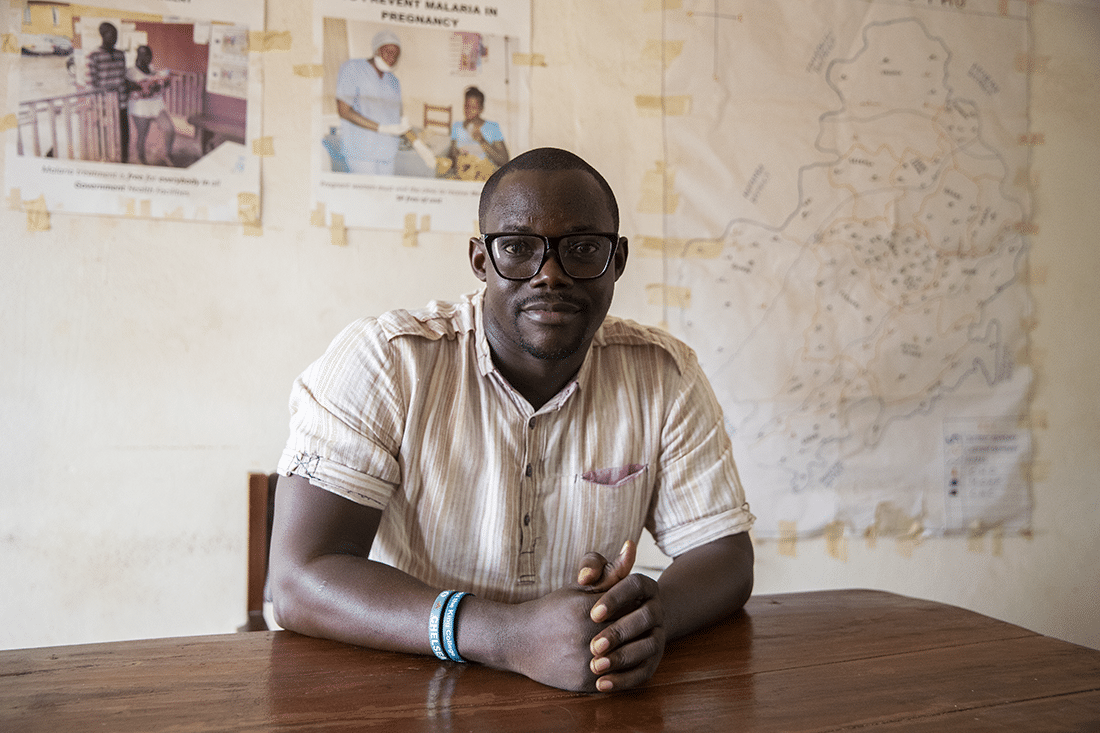

Nathaniel Soloku, a monitoring and evaluation officer at Bo District Health Management Team, has been involved with Project HOPE from the beginning of the program’s implementation. Soloku and his colleagues were initially skeptical of the KMC concept, and now recognize the drastic positive impact it has on newborn survival rates.

“The Kangaroo Mother Care program … seemed very strange at first to the mothers — and even to the doctors,” says Soloku. “No one really understood why hospitals should make space for a Kangaroo Mother Care unit. Now the mothers and doctors are very happy about it. It’s become routine and is the best practice for our mothers.”

Dr. Joy Nalley is head of pediatrics at Bo Hospital, and often spends her day training nurses at a learning lab established by Project HOPE and making rounds in the KMC ward and Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU). The SCBU is the hospital’s version of a neonatal intensive care unit, but not nearly as equipped. They have some incubators, but not enough for all of the babies.

“Before now, we used to think these babies were doomed,” she says. “We didn’t know how to care for them. Now, there’s something you can do for your small baby. It brings back the mother’s confidence. She’s the one in charge. We’re mostly just support… We help them to build their confidence before they leave.”

The maternal and neonatal wing of Bo Hospital has come a long way since the start of our intervention. The staff is pleased to finally have a dedicated space for the learning lab, KMC ward and SCBU. They’re also set up with solar panels and batteries now, thanks to a collaboration with the Sextant Foundation and the ministry of health, which keep the lights on and equipment working when the power is down. (The hospital frequently loses electricity, especially when there are heavy rains.)

Even with the improvements, the state of facilities is still wanting and the most basic resources are limited. There often isn’t enough food for mothers staying at the hospital. They’re forced to make the choice between leaving their babies to go get meals, or go long periods of time without eating — neither option ideal for a nursing mother.

There’s no doubt that there is still great need and a lack of resources. We’ll continue our work to strengthen the capacity of health workers to better serve their patients, as KMC continues to make a difference in what matters most – saving lives.

As Musu and her new daughter head out the door for home, Haja Sannoh, 16, and her new baby girl Salamantu return to the hospital to visit the nurses. Salamantu, now three-months-old, spent a week in the SCBU after being born at just 1.5 kg (3.3 pounds). She was then transferred to the KMC unit, and they were discharged once Salamantu had gained enough weight. Haja was proud to return and show off her healthy baby girl to the nurses who had cared for them. She’s grateful for what she’s learned, especially as a first-time mother, and has big dreams for her daughter: “I want to see my baby girl become president.”